--

Angéle Shami Maranian

b. 15 May 1915

Keskin, Ottoman Turkey

d. 27 March 2007

Hichingbrooke Hospital (nr. Cambridge), England

Photos:

Keskin 1914

Photo1.jpg 157.36KB

29 downloads

Photo1.jpg 157.36KB

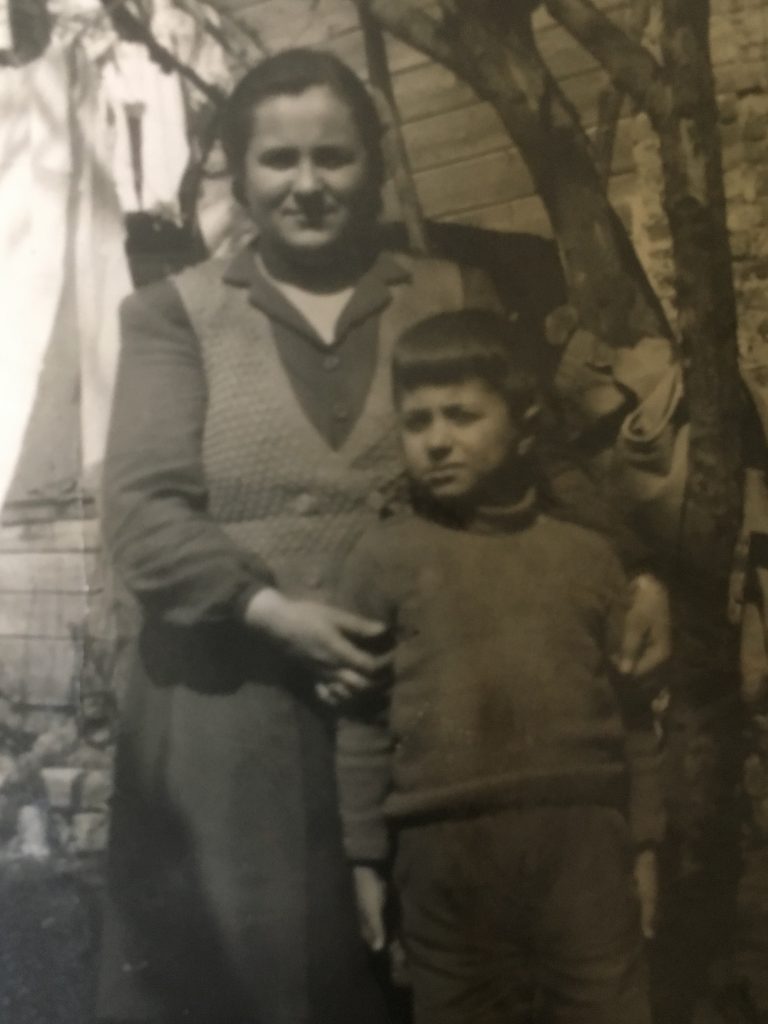

29 downloads Hayguhi/Reine, Shami/Angéle in Belgium, 1920s

photo3.jpg 270.61KB

19 downloads

photo3.jpg 270.61KB

19 downloads Horyeghpayr l'Abbe Jean Nalbandian

l__abbe.jpg 692.27KB

23 downloads

l__abbe.jpg 692.27KB

23 downloads l__abbe2.jpg 278.24KB

17 downloads

l__abbe2.jpg 278.24KB

17 downloadsAngéle with mother Sultan, sisters, and l'Abbe

photo4.jpg 93.22KB

19 downloads

photo4.jpg 93.22KB

19 downloads The Schloss, Liebenhau, Germany WWII

photo8a.jpg 366.09KB

13 downloads

photo8a.jpg 366.09KB

13 downloadsMaurice and Angéle with newborn twins at internment camp in Vittel, France, 1944

photo10.jpg 179.52KB

23 downloads

photo10.jpg 179.52KB

23 downloads Life in suburban London, 1950s

photo18.jpg 668.04KB

25 downloads

photo18.jpg 668.04KB

25 downloadsTrip to Ankara 1970 to see sister Akabi

photo29_1970.jpg 282.17KB

25 downloads

photo29_1970.jpg 282.17KB

25 downloadsTrip to Liege, Belgium 1995 to visit convent attended as a girl

photo44_1995.jpg 1.11MB

27 downloads

photo44_1995.jpg 1.11MB

27 downloadsA few months before she passed away

Nana_hospital_resize.jpg 198.33KB

20 downloads

Nana_hospital_resize.jpg 198.33KB

20 downloadsand here is a video of Keskin I found on youtube: Keskin

Early Years: Turkey, Lebanon, Egypt, Belgium

Angéle Maranian was born Shamiram Nalbandian in May 1915 to an Armenian Catholic family in the town of Keskin Denek Maden, located in the Ankara vilayet of Ottoman Turkey. Her father, an engineer in the local mines, did not survive the events of 1915, and the severe wartime conditions left her mother without the means to take care of Angéle and her three sisters. Wanting to give the girls a better life, around 1919/1920 the mother put Angéle and her next oldest sister Hayguhi/Reine (b. 1913) in the care of a group who were departing the area. They had promised to put the girls in school at a place called Zincidere (possibly in Kayseri). Thus the girls left their mother and two sisters for what was to be the beginning of a whirlwind set of events that would take them first to other parts of the Middle East and then to Europe.

It is unclear what happened next but after about a year in Zincidere, they were taken as part of a group to the southern Turkish port city of Mersin by horse and cart. Angéle recalls the horse and cart falling over on the way to Mersin. At Mersin they boarded a boat to Beirut. Arriving in Beirut after three days of travel by boat during which the boat sank and they had to be rescued from the water, the sisters were split up and sent to different camps. Angéle remembers the name of her camp as "Souk", while Reine’s was in Jounieh. The camps, run by American relief organizations, were full of orphans from many different backgrounds. They had no shoes, and they slept on the floor as there were no beds. After about six months Reine petitioned for the sisters to be put together, and they were reunited staying in Jounieh. By this time the girls had lost all contact with their mother, who was still in Turkey. One day however, a letter arrived at the camp from their mother, the first contact they received from their mother since they had left Turkey more than two years earlier. Reine gave the letter to her younger sister to hold onto while she searched for someone who could read it for them, but a strong wind blew in and snatched the letter from young Angele's hand. It was lost and they were devastated. The sisters remained in these shelters for another two years.

One day an announcement was made in the camp that there was room for Catholic children in an Armenian orphanage in Alexandria, Egypt. Angéle and Reine requested to go, and arrangements were made for their travel. Thus the two sisters arrived in Alexandria in 1923 at the ages of 10 and 8. The orphanage was run by wealthy Armenian tobacco growers named Matossian, who brought Armenian Catholic nuns from Rome to take care of the children. The years they spent here were by far the happiest of their lives so far. It was a clean and beautiful place, and they were there with other orphaned Armenian children. They slept in beds for the first time they could remember, and went to school in the orphanage, being taught to read and write in Armenian. In the afternoons the nuns took them to the seaside. They would end up staying in this orphanage for four years.

Unbeknownst to them at the time, their mother in Turkey was frantically trying to locate her lost daughters. The sisters' paternal uncle was a Catholic priest who had studied at the Mkhtarist seminary in Venice and had risen to a prominent position in the Armenian Catholic Church. Known as l'Abbe Jean Nalbandian, he had already become well known in Europe for bringing Armenian orphans from the Middle East to Belgium and France. Their mother contacted him to enlist his help in tracking them down. So it was that one day in 1927, an Armenian priest from Cairo came to the orphanage in Alexandria to ask the girls if they had an uncle named Nalbandian. "Yes", they said, "we have an uncle named Nalbandian, but we don't know where he is." Surmising that these may be the sought-after sisters, he told them that their mother had been looking for them for almost ten years, and that their uncle wished to make arrangements for them to relocate to Belgium. Soon thereafter, they packed the few belongings they had, said an emotional goodbye to the nuns and other children of the orphanage, and boarded a ship to Marseille. The journey took four days. In Marseille, they were met by a young priest and friend of their uncle's. The young priest asked them where their suitcases were. They explained that all they had were the bundles beside them. From Marseille they traveled to Paris, and were met by two of their cousins, Marcel and Pascal and their mother. These cousins' father had also been killed in Turkey during the events of 1915. After about three months in Paris staying with Marcel and Pascal and their mother, the uncle brought the girls to Belgium, putting them in an orphanage first in Tournais (1 year) and then in Brussels (1 year).

It was at the end of this second year (around 1930) that the uncle made arrangements for their mother Sultan and youngest sister Yeghisabet, still in Turkey, to settle in Belgium. Soon after, their mother and sister arrived in Belgium, leaving the oldest sister Akabi, already married, in Turkey. Angéle and Reine were now reunited with their mother after having spent most of their childhood as oprhans. There was much happiness upon their arrival, but to their dismay they quickly discovered that they could not communicate with each other. The sisters spoke only Armenian and French, and the mother and younger sister spoke only Turkish. Eleven years of separation had created a cultural distance between them. Nevertheless, the sisters recovered their lost Turkish language skills, and life acquired a degree or normalcy.

Angele was sent to further her schooling in a Catholic convent in Liege, Belgium, while Reine began work as a seamstress. Reine married Renee and their daughter was born in 1938. It was during this period that a member of the Armenian community of Brussels approached the sisters' mother, explaining that his son was looking to meet an Armenian girl. The son was Maurice Maranian, born in Manchester, England in 1908 to an English mother and an Armenian father. The Maranians were a family of Armenian shipping merchants who had settled in Manchester in the 1860s. One part of the extended family lived in Manchester, while the rest lived in Ottoman Turkey, where the family owned land in Samsun, Trabzon, Erzerum, and Batum (Georgia). Although Maurice was born in Manchester and was half English, he spent his childhood in Istanbul, attending the Armenian schools in Istanbul (such as Essayan). Armenian and Turkish were his first languages. His English mother died in childbirth in Istanbul when he was young, and was buried in the Armenian cemetery on the island of Kinali near Istanbul. After the massacres, the family fled to Belgium, and by the time he met Angéle, Maurice had a small business repairing carpets in The Hague, Holland.

World War II

The marriage took place in Brussels on August 29, 1939. They intended to spend their honeymoon in England planning to see Maurice’s brothers Edward and Steven and their wives. However, a week after the wedding, war was declared. Mobilization started, so they had to return to Maurice’s home in The Hague, Holland. They took what was to be the last train from Brussels to Holland before the borders were closed due to the occupation of Belgium by the Germans. Maurice had his carpet business in the Hague and he was doing reasonably well. At this time they received a letter from the British Consulate advising them to evacuate back to England. However, Maurice still had business to take care of with payments due and they decided to stay. The Germans attacked Holland with devastating bombing and the country was overcome in four days. During this time Maurice and Angéle went to the shelters. Angéle recalls going to see Rotterdam flattened following the heavy bombing by the Germans.

In June 1940, Maurice got a notice from the Germans to go to the “Komandature”. After taking care of some business errands he arrived there and soon realized that he was with other British nationals and that his freedom was over. Angéle received a call from a friend to say that Maurice had been arrested. She went to see him and he asked for a pair of pajamas and cigarettes. The Germans told the relatives of the men to come back at 6.00 am the next morning. When Angéle came the following morning, along with the other relatives, all the men had already gone. She found out two months later that Maurice and the other men had been sent to a place called Altmar where there were barracks. Relatives were allowed to see the men for one hour every month and she managed to travel there on one occasion.

Angéle was left on her own in The Hague with little knowledge of Dutch. For safety reasons she was told to leave The Hague since it was near the coast line. A Belgian friend told her to go to see a priest for help since she was Catholic. The priest gave her a letter to go to a convent in Amsterdam and so she packed up what she needed leaving the business and all their possessions back in The Hague with the landlord. The Nuns said that normally they could not keep married women but because of the war and her circumstances, she could stay. She stayed about two to three months in a building on her own. There was still some bombing going on and she spent many nights petrified. Angéle was also frightened of the German soldiers who did not have a good reputation. She was required to go to the “Kommandature” every week. During this time she supported herself with an allowance she received from the British once a month and from sewing that she did. She usually traveled by bike for her errands.

Angéle was trying to make arrangements with another French lady to find a flat to live together in when she was notified on December 19, 1940 to go for a special visit to the “Kommandature”. She had been working doing some sewing and so that morning, as usual, she went on her bike to do her errands and then arrived at the “Kommandature”. Soon, many others arrived such that eventually there were five hundred or so who also had British citizenship. She would now also be interned and her freedom would be over. She also had to leave behind her bike which she loved. For Angéle, being imprisoned due to her British nationality was ironic since she had not yet been to England and did not speak English. Although some British were discharged, the Germans maintained that she had to be arrested since she was legally a British subject married to a British citizen.

With the other women internees, she was sent by coach to the barracks at Altmar where Maurice and the other men had been. However the men had gone and they had no information as to where they had been sent to. Eventually they found out that the men had been sent to Tost, near Leipzig close to the Polish border, and they were soon able

to start corresponding with them. The women stayed in Altmar for about three months. At the barracks, life was hard with poor food and no proper toilets. They were required to work, mostly in the kitchen. Most of the other lady internees were Dutch speaking and so she began to learn Dutch earnestly. Angéle met Mrs. Gibson, who had lived in Indonesia and who became a life long friend until Mrs. Gibson’s death over forty years ago.

Eventually the internees left Altmar and were sent by train to Germany. They were in a cattle wagon and it was very uncomfortable with most of them getting swollen legs. People were crying, and some were hysterical, particularly the British Jewesses, who thought that they were being sent to the gas chambers. The train stopped at Aachen where they were given salted pea soup. They changed trains at Cologne having an hour to stretch their legs. This time the train was much more comfortable. Eventually the train came to Ravensburg where the SS were waiting. The SS shouted their orders and they were then taken by coach to Liebenhau, southern Germany.

The buildings at Libenhau consisted of a castle (called the “Schloss”) and four big buildings. It was run by nuns and was being used to attend to two to three thousand mental and disabled patients. Hitler gave the orders for six to seven hundred of the mental and disabled patients to be exterminated with needle injection to make way for Angéle’s group of internees. There was already about three hundred British people from Poland. Others came from Greece, Czechoslovakia, Belgium and Germany as well as the five hundred or so from Holland. The buildings at Libenhau were large and there was a barbed wire fence around the grounds. The food was very bad, mostly “ersatz” bread, but the internees only had to do cleaning and work once a month in the kitchen. The nuns did most of the work including working in the fields and also got some help from the German mental patients that remained there as well as the internees. The guards were mostly old German soldiers who were quite nice since they said that they were well treated by the British in World War I after being captured. After six to eight months, the internees received Red Cross Parcels from Switzerland comprising margarine, meat loaf, dry biscuit, tea and biscuits and money to buy things like toothpaste. Angéle was in a room with seven other ladies (Eileen Jarret, Rita Litenhoff, Anita Cohen, Mrs. Gibson, Mrs. Green, Barbara Cornfield and Sophie Newman). The room was comfortable with feathered quilts and feathered mattresses for their beds. By much coincidence, Angéle met her school friend from Liege, Helen Eliot, whose English family had lived in Belgium before the war. Life was hard but there was a lot of spirit and camaraderie. They were able to go out for walks once a day within the grounds and they constantly played cards, usually bridge. They also organized theatrical events once or twice a year including a production of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Angéle was in charge of a sewing room to help to make clothes for the show and dressing gowns. She also said that the Germans in her area, who were mostly Catholic, did not want the war and wanted Germany to lose.

Internees in the men’s camp and the women’s camp petitioned for the husbands and wives to be together in the same location. They argued that the German husbands and wives, who were being interned by the British, were together on the Isle of Man. Eventually the Germans agreed and on January 22,1943, Angéle, along with many other married ladies, were sent to a camp in Vittel, France. However none of the women from Angéle rooms in Libenhau went to Vittel since they were either unmarried or widowed.

The Germans confiscated several hotels to house the internees. The internment camp at Vittel was also formally a hotel, with tennis courts and a spa. Its drinking water is still renowned today. The internment camp at Vittel housed about two thousand internees, mostly Americans, Russians, British and also Jews from Poland and Austria who had falsified British and American passports. Part of the hotel was used as a hospital. Angéle was in a comfortable room on the fourth floor with another lady called Jeanne Russell and a very kind French Lady of peasant stock who could not read or write. She befriended a French lady who persuaded her to work in the kitchen serving the soup. Workers helping in the kitchen got special privileges and were allowed to go as group with a guard to the local village to buy things they needed. They also used to barter with the French farmers for cigarettes and chocolate.

The men, including Maurice arrived on August 8, 1943 and there was enormous joy. Angéle found that that her husband had changed somewhat. His hair had receded and he seemed to be greatly affected by the rigours of being interned. Angéle on the other hand had put on weight. The married couples were placed in villa-type accommodation and Angéle and Maurice’s room was number 330. It was quite comfortable with a large sized kitchen. They continued to get Red Cross parcels every week which sustained them particularly for breakfast. They also received an allowance from the British once a month. Life was relatively comfortable and Angéle was able to play tennis and netball. Maurice and Angéle found another Brtitish Armenian family originally from Manchester, the Gumuchian family, consisting of a mother and two daughters. The eldest daughter, Stella, was conductor of the orchestra and the younger daughter, Sonia (still alive and now living in Paris) also played in the orchestra and performed in shows.

Angéle started to feel sick and went to see her kind Jewish doctor. He prescribed her medicine but it seemed to make her feel worse. They still could not find out what it was but eventually after four months they realized that she was pregnant and that she was to expect twins. Tragically, in the spring of 1944 the five hundred or so Polish and Austrian Jews were found out by the Germans to have false documents. These Jews were very distinguished and prominent people from their society. Many of them committed suicide to avoid being sent to a concentration camp. The rest of the internees strongly protested the terrible treatment of the Jews but were punished having to stay two nights in their rooms in the dark. This all happened about the same time that Angéle gave birth on April 16, 1944 to twins Michael Manouk and Margaret Araxie. Angéle and the twins had to stay in the hospital for three weeks since the babies were premature. Michael in particular was not responding well. Mother and the babies were looked after by German, French and British doctors. During her stay she recalls hearing ambulances coming frequently to the hospital carrying those who had successfully or unsuccessfully committed suicide either by jumping out of windows or cutting their wrists. In the bed next to Angéle was a Jewish lady from Austria who also gave birth to a child. The lady cried inconsolably since all her relatives, including her husband and mother, had been sent to concentration camps and she was left behind with her child. Sadly, she later committed suicide. Angéle has told this story many times.

The doctors said that Angéle could leave the hospital and leave the babies there. However she decided not to do so on the advice of others who feared that the doctors would somehow allow the babies to die. After leaving the hospital with the babies Angéle was helped by two sisters Rita and Sophie to look after them. Apparently there were about thirty babies born in the camp.

From the radio, the internees heard that the Americans and British had landed on June 6, 1944 and they subsequently followed the gradual retreat of the Germans. Around September of 1944, the area around Vittel was being liberated and much fighting took place around the camp. The German soldiers went to the mountains during the day for protection. There was a lot of bombing by the Americans and the French Resistance which went on all day. The German Komandant of the internment camp, known as Monsieur Stephan, made everyone go to the shelter. Angéle was almost killed when she went back to the room to get food for the babies and shrapnel burst into the room. The Americans and the French Resistance temporarily succeeded in liberating the area, including the camp, and the internees threw them flowers, chocolate and cigarettes. The Germans came back and attacked the area, but the French Resistance had changed all the road signs and the Germans were confused. This time the Germans were trapped and defeated. Monsieur Stephan was killed. Angéle saw many of the German soldiers being kept as prisoners in stables and Maurice went to the fields where many soldiers lay dead. She often said that they suffered too and has since throughout her life been appalled at the modern wars that have taken place knowing the terrible human suffering they bring.

After being liberated, Maurice, Angéle and the twins, along with the rest of the internees, stayed at Vittel for about three weeks or so. The British Consulate came and they were told they would be in England within a day. On October 16, 1944 they gathered their few possessions and were taken to Tours in France in a group of twenty one refugees. Tours was an airfield with temporary hospitals for the wounded. Instead of staying a short while in Tours, they ended up staying four nights sleeping on stretchers in a large tent waiting to be put on a plane to England. The Americans looked after them well and they were well fed. At one point they ran out of nappies for the babies so the Americans gave them four pillow covers to use. The Germans started to bomb again though and the American general said that it was too dangerous for them to stay. The group of twenty one refugees then traveled to Paris where many soldiers and refugees had gathered. They arrived at noon at the railway station and waited until 6.00pm when they were eventually taken to Monmatre Hotel by the British Consulate. The hotel had no lights so they had to stay in the dark. The following morning, the French Red Cross, who were very good to them, gave then some milk and money. To buy food you needed coupons which they did not have and so they had to go to the soup kitchens for the poor. They stayed at the hotel for four days.

After their stay the Monmatre Hotel, they were sent by the British Consulate by coach to Bourjais Airport which was still operating despite being flattened. They arrived at the airport at noon and had to wait till 6.00pm before being flown to Northholt airport near London on a Dacota plane with the rest of the group of twenty one refugees. After much

interrogation at Northholt airport, they were sent to a refugee center in the center of London. They were photographed by the press in the refugee center. The following day, The Daily Mirror wrote an article with the heading “Twins, born in Hun Camp are freed” and the Evening News showed photographs of Angéle and the twins with a title “Born in Captivity, Free in London”. Maurice went to see his sister in laws in Ruislip who lived on the same street but found neither of them at home since they were at work. He left a note to say that the family had arrived. When they arrived home that day to find the note they were overjoyed. Soon the family was reunited with Maurice’s brothers and sister in laws e, Edward and Rebecca and Steven and his first wife Gladys and their son Anthony. They had not seen each other for six years. Maurice’s brothers Edward and Steven, had spent much of the war with the British 5th Army in Egypt.

World War II Postscript: An interesting additional item to the World War experience is with regard to a post card sent by Maurice dated December 7, 1943 from the internment camp in Vittel to his landlord, Mr Ockemulder, in The Hague, Holland. Mr. Ockemulder only received the postcard some thirty six years later on November 30, 1979. An article in the Dutch Newspaper Haagsche Courant, regarding this astounding occurrence, was published in the newspaper’s December 4, 1979 edition. It is possible that the postcard was left in a corner of the local post office in Vittel only to be found decades later.

Life in England - note: can skip this section, mostly family information

The family first settled in a small bungalow adjacent to Norhholt Airport in South Ruislip in Middlesex, shared with another family, being helped a lot by the Bowman family, Janet and George together with their daughter Beryl, who were friends of Edward and his wife Rebecca. The family then moved to a temporary accommodation called the Nissin hut in Eastcote, Ruislip, Middlesex where Peter was born on July 8, 1948. In November, 1948, the family moved to a house on Field End Road in Eastcote where Angéle would live for the next fifty six years. For the most part these were very contented years after all the hardships and difficulties of her early life. In 1950, Angéle’s eldest sister Akabi and her daughter Helen, still in Turkey, came to visit the family in Eastcote. Angéle had not seen her sister since leaving Turkey in 1919/1920. Maurice worked at a carpet company in London specializing in repairing oriental carpets. There were often annual trips to Belgium to see Edward and Rebecca, Reine and her husband Renee and their children Liliane and Guy, Elize and her husband Lousienne and their son Jean Jacques, along with Maurice’s half sister Sona and her husband and daughter Chouchanic. There were also memorable trips to the seaside with a social group run by the Bowmans. It was a nice neighbourhood and the family made many friends including the next door neighbours the Cummings including their daughter Sylvia, the Aldcrofts including their daughter Gaynor,next door neughbours the Hopcrofts, the Mills family and others in Eastcote including Molly Lees and her family. Angéle’s mother passed away in 1959 and her uncle, the Catholic bishop, passed away in 1963. He had been well known in Belgium, having been an acquaintance of the Belgian Royal family and the Pope of that time, and lived a very full life, which included looking after Armenian orphans after World War I.

Unfortunately, Maurice developed a heart condition in 1960 and was in hospital for six weeks. He had to reduce his work hours along with other cautionary measures. Around that time, Angéle started working in a taylor’s shop in Harrow doing alterations and repairs. She worked there until the mid-1970s. Sadly, Angéle’s youngest sister Elizabeth died suddenly in 1966. Margaret was married to Gerry Adley in 1968 in Pinner, Middlesex. In 1970, following the marriage of Guy and Chouchanic, Angéle, her sister Reine, and Peter went to Turkey to visit Akabi and all the family, staying in Istanbul and Ankara. Peter met his future wife Srpuhi on this holiday. Michael was married to his first wife Madeleine in Pinner, Middlesex during the summer of 1971. Trajedy was to occur soon after when Maurice died on September 16,1971 of a heart attack on the return leg of a journey to Brussels to visit Edward and Rebecca and she became a widow. This occurred just four weeks before Angéle and Maurice’s first grandchild, Samantha (daughter of Margaret and Gerry) was born. Peter was married to Srpuhi in Istanbul in 1973. Soon after, Maurice’s cousin Marina, who never married, came to live with Angéle. Other grandchildren came along; Natalie (first daughter of Michael and Madeleine) in 1974, Tanya (second daughter of Margaret and Gerry) in 1975, Melanie (second daughter of Michael and Madeleine) in 1976, Paul (son of Peter and Srpuhi) in 1978 and Lena (daughter of Peter and Srpuhi) in 1980. In 1974, Rebecca passed away and about a year later Edward came to live with Angéle in the house in Eastcote. Peter and Srpuhi and their children immigrated to Los Angeles in 1981, and Angéle came several times to visit them as well as Akabi and her large family, who had also imigrated to Los Angeles some years earlier. Edward passed away during the summer of 1983 after a short illness. Angéle had looked after him well during his stay at the house on Field End Road and he was comfortable and contented.

Akabi passed away in 1988 of cancer in Los Angeles followed sadly by her son Artin, with heart failure, later that same year. Margaret was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 1989 and with great sadness, passed away on August 1, 1990. Despite the great losses to the family that she endured, she remained a great source of inspiration and the center of comfort, caring and love. Around that time, Angéle started working in Beryl Bowman’s soft toy shop along with Beryl’s parents Janet and George. The shop in Ruislip Manor, seemed to operate as if it were in the 1930s. There was no till (just a plastic container) and no receipts, Even the takings were at 1930s level. Sometimes she’d come home and say we didn’t do very well today we didn’t sell anything. Other times it was “we did quite well today”; takings were just £5 or £10. Beryl devoted her life to helping the elderly and with the shop also having a hair salon it became a popular social focal point for some ladies in the Ruislip area. Working in the shop at a time when Margaret was seriously ill and also during the period following her death, provided Angéle with some alternative occupation at such a stressful time. Beryl, her parents and her husband were some of the dearest friends she had.

Marina, who lived with Angéle for many years during the 1980s and early 1990s eighties, passed away in 1994. Helen, Akabi’s daughter, lost a five-year battle with ovarian cancer on July 31, 1996. Angéle’s last trip to Los Angeles was in 1998 at the age of 83 when she came to attend her granddaughter Lena’s debutant ball. Over the years she found friends in Los Angeles, Gussy Hatzik and Mrs Sulujian that she got on with very well. She continued to work at Beryl’s shop until the year 2000, walking to the station and up and down the stairs at the stations until she was 85. Her courage and determination to make the most of life was inspirational. She was blessed with good health (brought on she said because of her clean living) and had an amazing amount of strength and energy, working until she was 85 years old. She was also never known to lose her temper (because she didn’t have one) and never been known to get angry.

In 2000, she attended Michael’s marriage to Jacqui and now had a bigger family with Jacqui’s children Sean and Lisa, Sean’s wife Lizzie, Lisa’s husband Billy and Lisa and Billy’s children Ethan, Tallulah and Honey which she got much pleasure from. In May, 2004, Angéle, along with Michael, Jacqui and Peter went to Brussels to see her sister Reine for the last time, who was in a retirement home. In August 2004, Angéle finally moved from her home in Eastcote to a retirement home in Cambourne, Cambridge, closer to Michael, Jacqui, Melanie, Natalie and Madeleine. Despite several months when she was quite homesick, she settled quite well in her retirement home and was a favorite amongst the residents and staff with her kind and caring ways. In September of 2004, her sister Reine, whom she was so immeasurably close to all her life, sadly passed away in September of that year and Angéle was able to attend the funeral, visiting Belgium for the last time.

In May, 2005 she celebrated her 90th birthday with a big gathering of family and friends. Included in the gathering were Ella and Spencer, Tanya’s children and Angéle’s great grandchildren. Liliane, her daughter Claudine, her husband Jean Paul and their children, Théa and Anaé, also came. Angela adored children and in recent times she had immense pleasure seeing her great grandchildren and step great grandchildren in her new retirement home. Having family around was what she enjoyed the most. Samantha once described her as a magnet; there was a natural attraction to her when the family got together. This was because of her unique personality, warmth and dedication to family and friends. You could call her in the middle of the night and she would still make you welcome.

Beryl sadly died around April 2006 not long after her parents passed away. This sad news was never to be passed on to Angéle as she would have been devastated.

In August 2006, Sonia Gumuchian, Angéle’s friend from the internment camp in Vittel, came to stay at Michael’s house and Angéle and Sonia had a reunion reminding them of their time together in Vittel during the war.

Unfortunately, Angéle fell and broke her leg on November 20, 2006. She never properly recovered from the injury and gradually declined. Despite the poor health she found herself, she still managed to smile and show her thanks to the nurses and doctors even if it was sometimes in French. She passed away peacefully at 5.15 pm on March 27, 2007. Her granddaughter Lena was by her side holding her hand. This was not long after Lena had reminded her of her incredible life story and also played a recording of Reine singing old Turkish and Armenian songs from their time together during those difficult early years.

Her long life was truly a life to celebrate. It was a life of survival from adversity which enabled her to become a source of love and affection to those who knew her. Those who knew her can only be grateful to have her been part of our lives and for the enormous inspiration she was and were enriched because of the special qualities she had. Always positive, always prepared to do whatever was necessary to make things a better place.

Her passing left a huge void in the family that will be impossible to replace. She was the centre point of the family, not because she wanted to be but because of who she was.