Armenian cemetery in Surat. | YashIsIn/Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 4.0]

There is a popular story among the Armenian diaspora in Russia about the role played by two members of the community in bringing Russia’s most prized Indian diamond to the country. The 189.62-carat Orlov diamond, which was found in Golconda in the 17th century, reached Russia in 1774 and was set into the sceptre of Empress Catherine the Great.

The Armenians believe that a member of the community from Surat, one Khoja Johannes Rafael, was responsible for the sale of the diamond to Hovhannes Lazarian, who bought it on behalf of Count Grigory Orlov (and hence the name). Orlov gifted the diamond to Catherine, with whom he had a long-term romantic relationship.

Some Russian historians dispute this story and say the diamond was sold to Lazarian by a wealthy Persian merchant. Even so, it is undeniable that Surat occupies a special place in the history of the Armenian diaspora, at one point acting as an important gateway for the community to India.

“It may not be generally known that the Armenians have been connected with India, as traders, from the days of remote antiquity,” Mesrovb Jacob Seth, historian and school master of Classical Armenian at the Armenian College and Philanthropic Academy, Kolkata, wrote in his 1937 book titled Armenians in India from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. “They came to this country by the overland route, through Persia, Bactria (Afghanistan) and Tibet, and we were well established in all the commercial centres long before the advent of any European traders into the country.”

While chroniclers from the court of Abkar recorded the presence of Armenians, who were invited by the great Indian king to settle in Agra, the Armenian community, which was focused exclusively on trade, left no written records of its activities or social conditions. “As a mercantile community they were deeply engrossed in commercial pursuits and had evidently no time for recording events, communal or general, possessing social or historical value,” Seth wrote.

Historians believe that Armenians began to settle in Surat as early as the 14th century, when the city was administered by governors appointed by the Delhi Sultanate. It was in the 16th century, however, that the city began to witness the emergence of a significant Armenian community that was engrossed in trade and had an active cultural life.

When news spread in Persia and Anatolia about Akbar’s invitation and a guarantee of religious freedom, larger numbers of Armenians began to move to India. While many chose Agra, some saw vast economic opportunities in the southern Gujarat port on the Arabian Sea.

These Armenian merchants in Surat would sell jewellery, precious stones, cotton, silk and other products to Armenian-owned merchant vessels from Basra and Bandar Abbas, which would export them to Egypt, the Levant, Turkey, Venice and Leghorn. Unlike others from West Asia who came to India without their families, such as Arabs, the Armenians moved with their wives and children.

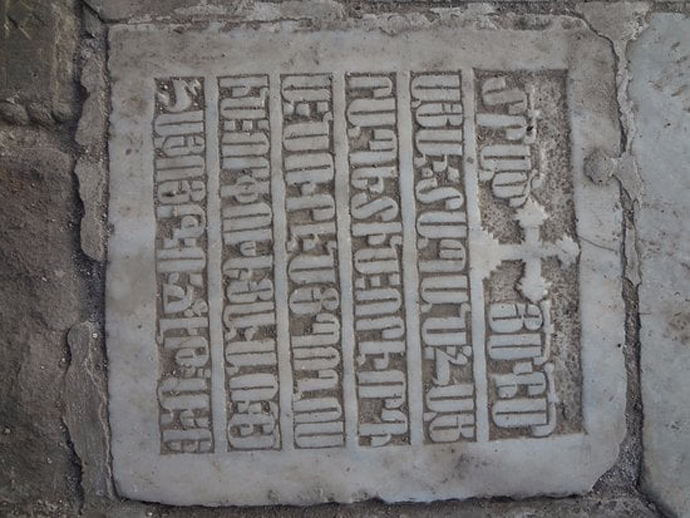

When Seth visited Surat in the late 19th century, he came across the tomb of an Armenian noblewoman named Marinas, who was the wife of an Armenian priest named Woksan. The tomb, which was erected in 1579, had an epitaph in ancient Armenian which read: “In this tomb lies buried the body of the noble lady, who was named Marinas, the wife of the priest Woskan. She was a crown to her husband, according to the proverbs of Solomon. She was taken to the Lord of Life, a soul-afflicting cause of sorrow to her faithful husband, in the year one thousand and twenty eight of our Armenian era, on the fifteenth day of November at the first hour of Friday, at the age of 53. Ye who see this tomb, pray to the Lord to grant mercy.”

The cemetery, near the city’s Katargam Gate, stands at the site of the first Armenian church in the city that was probably built in the 16th century. “According to an Armenian geographer the old Armenian church at Surat was destroyed by the Mughal governor (but he does not say when) at the instigation of the Turkish merchants who came to Surat, after their pilgrimage to Mecca, for the purpose of buying goods,” Seth wrote.

A second church that was dedicated to the Virgin Mary was built by the community in 1778 and managed to survive until the early part of the 20th century.

In 16th century, Armenians traders lived in Surat. Grave plaques in their Tombs have beautiful artistic motifs

Special concessionsWhen English merchants first arrived in Surat in the early 17th century, they were concerned that the Armenians had a complete grip on foreign trade from western India. But a confrontation was ruled out beause of the special status the Armenians enjoyed with the Mughals. So, instead, the English tried to develop a good working relationship with the Armenians and asked them to act as intermediaries.

“The English tried to win the confidence and cooperation of successful Indian-Armenians in order to secure their intercession with the Mughal court for trading privileges in India,” David Zenian wrote in a July 2001 article for the Armenian Benevolent General Union’s magazine. “The efforts of the English came to a head when an agreement was signed in London on June 22, 1688, between the East India Company and the ‘Armenian Nation.’”

The agreement was signed on behalf of the Armenian community by an immigrant from New Julfa (the Armenian locality of the Iranian city of Isfahan) named Khoja Phanoos Kalandar, who was then seen as the leader of Surat’s Armenian community. (The wealthiest Armenian merchants were given the title Khoja.) Being a tough negotiator, Kalandar managed to get several concessions for the Armenians. For one, the East India Company allowed Armenian merchants to travel and transport their goods to and from Europe on Company ships. For another, it granted them all the privileges it allowed its own and other English merchants.

The Armenian merchants “were also allowed to reside and trade freely in the Company’s towns and garrisons, where they could hold all civil offices and employments, equally with the English,” Mesrovb Seth wrote, adding that the English also allowed them complete freedom of religion. The privileges and benefits looked good on paper, but as history showed later, the English managed to almost completely supplant the Armenians.

Peak and declineThe Armenian community in Surat was its peak in the middle of the 18th century with a population believed to be as large as 200 people. At that time, one of the richest and most influential Armenians in the city was Khoja Minas, who owned ships that would sail between Basra and Surat, taking Indian precious stones to Europe. He was a contemporary of the merchant Khoja Johannes Rafael, who the Armenian diaspora in Russia credits with selling the large diamond to Count Orlov.

With the growth of Bombay, Madras and especially Calcutta as trade centres, the Armenian community in Surat began to branch out by the end of the 18th century. “The decline and dispersion of the Armenians at Surat must have been very rapid,” Seth wrote, adding that there were 33 merchant families in the city at the end of the 18th century. By 1820, there were less than 10 Armenians in Surat.

Among the few surviving members of the community, a woman named Hripsimeh Leembruggen (nee Voskan) managed to make a name for herself. The daughter of a wealthy merchant, she married Robert Leembruggen, a Dutchman who worked for the East India Company, according to David Zenian. Inheriting her father’s wealth, Leembruggen successfully ran her father’s businesses and expanded them until her death at the age of 55.

The Armenian-Dutch couple did not have any children. “Upon her death in 1833 she bequeathed all her fortune to Armenian religious, educational and charitable institutions, principally to the Armenian Church in Madras for the care of orphans,” Zenian wrote.

Surat’s Armenian church managed to survive till 1907, but regular prayer services were discontinued in the 1830s. Mesrovb Seth visited the church in January 1907 and was disappointed that it had fallen into disrepair. He wrote, “Alas for the departed glory and the vicissitudes of time! For by an irony of fate, the beautiful church, with historical associations, was, in the absence of devout worshippers, found in the indisputable possession of thousands of owls, bats, crows, cats, rats, snakes and scorpions which howled, screeched, and hissed ominously when the present writer, at the risk of his life, entered the sacred edifice where his revered grandfather, Seth Mackertich Agazar Seth, had worshipped during the last quarter of the 18th century.”

The church was torn down in 1907 by the wardens of Bombay’s Armenian church and converted into a children’s playground. Shops and small residential buildings came up on the ground with the passage of time. None of the buildings that were home to Surat’s Armenian community have survived.

The only reminder of the presence of the community in Surat is the Armenian cemetery, which has a well-preserved mortuary chapel that was probably constructed in 1695. The chapel contains the grave of the son of Khoja Phanoos Kalandar. When Seth visited the cemetery, he noted, “It may be mentioned that this is the only grave inside the chapel which shows the high esteem in which the deceased was held in high esteem by the Armenian community of Surat, for only great men – national benefactors and philanthropists – are buried inside Armenian churches and chapels.”

While the legacy of the community in places like Bombay, Madras and Calcutta is better remembered and celebrated, the settlers in Surat paved the way for Armenians to add to India’s rich fabric of ethnicities and nationalities.

Ajay Kamalakaran is a writer and independent journalist, based in Mumbai. He is a Kalpalata Fellow for History & Heritage Writings for 2022.

https://amp.scroll.i...g-home-in-surat