Armenians and Crusaders

#1

Posted 25 February 2001 - 11:15 AM

#2

Posted 25 February 2001 - 09:59 PM

#3

Posted 26 February 2001 - 03:46 PM

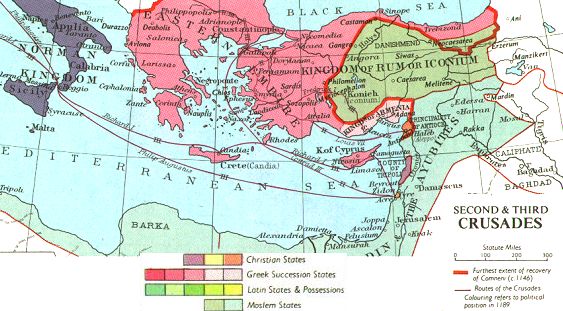

The Crusades took place during the period 1096-1291, and military expeditions were undertaken to recover the Holy Land from the Muslims. During the two-century period eight main Crusades ventured into the Middle East to fight of the yoke that the Seljuk Turks harnessed on Christians who attempted to visit the birthplace of Christianity. The Seljuk Turks, who occupied the region in the eleventh century, imposed all kinds of restrictions and persecutions on the Christians who lived in the area. In 1095 the Byzantine emperor, Alexius Comnenus, appealed to Pope Urban II for assistance against the Turks. The Pope preached for a holy war, or a crusade, and Europe responded with several different armies.

Armenia acknowledged the Crusaders with full support. Cilician Armenia, or Lesser Armenia as some historians referenced the region, had formed principalities in Cilicia after Armenia proper had fallen to the wrath of the Seljuk onslaughts. From 1080 Armenian Princes from the Rupenian, Oskinian, and other families established small enclaves within the protective mountain ranges that surrounded Cilicia on three sides and the Mediterranean Sea to the South. In time the area became a stronghold of Armenians led by the Bagratid Armenian Prince Ruben.

When the first Crusaders arrived in Cilicia, they were graciously and pleasantly surprised by the strong Christian principality. The Armenians were generous supporters of the Crusaders and did whatever they could to help the ¡§soldiers of Christ¡¨ free the Holy Land.

The First Crusade (1096-1099) - The first Crusade made up of several European armies captured Nicaea (1097), Antioch (1098), and Jerusalem (1099). The Crusades established three principalities, Antioch, Edessa, and Tripoli and the Kingdom of Jerusalum. Armenians provided significant provisions and military equipment to the first Crusade, especially in the siege of Antioch.

The Second Crusade (1147-1149) - The second Crusade formed due to the persistent attack by the Muslims and the recapture of Edessa (1144). However, instead of attacking the Muslim power (the state of the Emir Nur al-Din) that was most threatening to the Crusader states, the Crusaders attacked the small Muslim city-state of Damascus. a state which had previously allied with the kingdom of Jerusalem against Nur al-Din¡¦s father. This Crusade led by the kings of France and Germany failed to regain lost territories. The Armenians and Crusaders continued to assist each other in their battles against the infidels.

The Third Crusade (1189-1192) - After the fall of Jerusalem in 1187, led by Saladin, the sultan of Egypt (Saladin was a Kurd by birth), another cry arose to save the Holy Land. During this Crusade Levon II and King Richard invaded and conquered Cyprus, which had broken away from the Byzantine Empire under a renegade relative of the former ruling house. Fredrick I, Emperor of the Roman Empire, planned to thank Levon II for Armenia¡¦s assistance during the Crusade, and present Levon II with a crown. Unfortunately, Frederick had a fatal drowning accident, and Levon never did receive the crown. However, nine years later (1199), Baron Levon II became Levon I, King of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. The Armenian Catholicos as well as the Papal Legate consecrated his coronation. Many alliances formed between the Armenians and the Crusades, resulting in Armenia becoming a vigorous Christian state where industry, trade and commerce thrived. An interesting sidelight to the third Crusade was the marriage of Richard the Lion Hearted in 1911. Levon II who was not yet King of Cilician Armenia was Richard¡¦s ¡§Best Man.¡¨

The Fourth Crusade (1202-1204) - The fourth crusade did very little except to sack and plunder Constantinople in 1204 much to the horror of the Pope. The ravaging was disgraceful. The Armenians had no part in the sack and plunder. Initially, the Byzantines were happy to see the Armenians in Cilicia, because they were a buffer between them and the Seljuk Turks. Later they thought the Armenians were becoming too powerful.

The Fifth Crusade (1215-1219) - The fifth Crusade¡¦s goal was to capture Egypt, but the drive was unsuccessful. The pathetic failure of the Children¡¦s Crusade in 1212 ignited the religious fervor of the fifth Crusade.

The Sixth Crusade (1228-1229) - Led by the excommunicated Roman Emperor Frederick II, the ¡§Christians¡¨ on the sixth Crusade were allowed by the Sultan to repossess Jerusalem in 1229, although they had to agree not to refortify it. During this time it was becoming clear that the great age of the Crusades was over. The Christians were able to maintain Jerusalem only until 1244 when Muslim soldiers fleeing the Mongols again regained the holy City. While the Crusades were being unsuccessful, the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia under Hetum I gained international status and was trading to major ports in the Mediterranean and to countries in the East.

The Seventh Crusade (1248-1254) - By the seventh Crusade many of the Crusaders had forgotten the purpose of their long journey. Rivalry for power and possessions soon caused problems among the Christians including the Armenians. Relationships were going sour and the Muslims were regaining more lands. The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia under Hetum I had managed to make some alliances with the Mongols during this period. Together with the Crusaders and Mongols who at first were open to Christianity, the Armenians were able to defeat the Seljuks in several battles.

The Eighth Crusade (1270) - The eight Crusade to Tunisia rather than to the Middle East, was the last major Crusades, and also was unsuccessful. Throughout the entire period of the Crusades, lesser Armenia was literally in the middle of successes and failures of the Latins. Inevitably the influence of the Europeans intermingled with the culture of the Armenians. Intermarriages of the Armenian Princesses with the Frankish nobility were extremely common. The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia had become very much a part of Europe. By 1291 the Muslims had regained all the territories of the Middle East except kingdoms of Cilicia and Cyprus. Lesser Armenia was able to maintain its boundaries until the Mamluks conquered the fortress of Sis in 1375. After the fall of Sis the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia was no more. Levon V, the last King of Armenia, was captured and taken prisoner to Egypt. He retired to Paris after a sizable ransom was paid for his release. Only the Catholicate of Cilicia, which at the time was led by the Catholicos of all Armenians (the Seat of the Armenian Apostolic church had transferred to Hromkla, Cilicia in 1147), was able to maintain some semblance of Armenian government. In 1441 the Holy See of all Armenians transferred back to Etchmiadzin. The Catholicate of the Great House of Cilicia remained in Cilicia until 1921 when it officially moved to Lebanon. From 1921 to 1929 Catholicos Sahag II traveled throughout the Middle East, as he had no permanent home.

Sourse:Armenian Heritage

[ February 26, 2001: Message edited by: surorus ]

#4

Posted 26 February 2001 - 04:12 PM

1096

Meanwhile a regular army was being organized, of armored knights on horseback, foot soldiers and many servants, priests, a bishop and even pilgrims, including women and children. Each of four units had its leader: Duke Godfrey of Lower Lorraine with Walloon speaking Frenchmen and Rheinlanders, Count Raymond of Toulouse and Bishop Adhemar the bulk being southern Frenchmen, Duke Robert son of William the Conqueror with northern Frenchmen who was joined and superseded in Constantinople by Hugh brother of King Philip of France, and the Norman Bohemond and his nephew Tancred with southern Italians rather well-experienced in battles against both Saracens and the Greek army. Godfrey reached Constantinople in 1096. Raymond, Robert and Bohemond arrived in 1097.

Constantinople

1097

What was the Emperor of Constantinople to do with this horde? Before he had an army principally of mercenaries whom he had to pay; now with the Crusaders he had a "free" army, but much too free to please him and without military direction from generals on down. They were far from a disciplined army, without a true military command and appeared to the Greeks as little more than barbarians. The only thing which united the Crusaders was the common objective to free the Holy Land from Moslem rule. The emperor needed to get rid of them and transport them across the Bosphorus as soon as he could. He designated sites outside the city for their encampment because they were a danger to his city. He didn't think they would ever reach their objective, much less live through battles with the Seljuks who had defeated his own army, yet he had to get them to agree that any place they recaptured would belong to him. Negotiations took months, but eventually all agreed except Tancred, and the emperor provided boats to take them across the water.

Nicaea

Nicaea is just across the Bosphorus and was in firm control of the Seljuks even though a majority of its beleaguered citizens were Christian. Here the Crusaders found themselves face-up against walls the likes of which they had never seen before. Writes Harold Lamb :1

These walls baffled the Crusaders. Hitherto the fighters from the West had to deal with low earth or wooden ramparts. Sometimes they faced a single wall of stone... Nicaea had been a stronghold of the Romans, and the solid masonry six feet thick had hardened to the consistency of stone. One quarter of the walls fronted the lake, and here&emdash;lacking boats&emdash; the Crusaders could do nothing. From one edge of the lake to the other a moat circled the fortification. Behind the moat rose a narrow wall, about twice the height of a man, with small towers. About fifteen paces behind this stood the main defense, the great wall with more than a hundred towers.

Before the siege of the city had actually begun a horde of Seljuks coming to reinforce Nicaea made a surprise attack on the Crusaders. The Crusaders had no time to put on their armor or saddle their horses, but grabbed their pikes and swords and by shear ferocity and steadfastness in one days' heated battle put the Seljuks on the run.

The fortress, however, was another matter, too high to scale, too strong to tear down, and with one side open to water, the Turks could not be starved out. Eventually the Emperor's navy gained entrance to the open side and made a deal with the Seljuks that the victory would be his and not the Crusader's. The Crusaders were surprised when dawn broke to see the imperial flags floating from the towers. The emperor provided the Moslem leaders with safe passage out so they would be unharmed by the Crusaders.

Not a few Crusaders were disappointed because of their losses in battle and felt cheated out of the spoils of war by the emperor, but he paid off the leaders (not before they swore further fealty to him) and there was no trouble.

The emperor didn't dare let the Crusaders into the city; he knew they would tear the place apart, but the Crusaders, still on a holy pilgrimage, wanted to pray in the churches, so he let in every 10th person on different days. We have not found out in what these "prayers" consisted. There were many Latin-rite priests among the Crusaders; did they offer Masses in the Greek churches? Very likely. Certainly they offered Mass especially on Sunday, but where? The point is: the "division" of a few years before (1054) had not yet taken place. In practice there was no distinction between "Catholic" and "Orthodox".

When the Crusaders got ready to continue their journey, the emperor to protect his interests appointed General Tacitius and a small Greek army to accompany them. Were there Greek priests with this army?

Dorylaeum2

Of course the Crusaders, by now swelled to about a half million, following their own leaders, broke up into separate armies and journeyed a day or so apart. On July 1st the Seljuks again descended on the advance guard, intending to kill them all just as they had done to Hermit Peter's "army". The guard would have been slaughtered by the shouting, racing Mongols were it not for reinforcements who came up from the rear. The knights in heavy armor on large horses at first were no match for the smaller Mongols on fast little horses, but there were so many Crusaders, and they held their line in stalwart fashion and finally routed the Seljuks, never to be bothered by them again.

A Death March.

The Crusaders &emdash; knights, foot soldiers, servants of all kinds, priests, pilgrims and stragglers&emdash; continued through Asia Minor but it became a death march for many of them in the salty desert. The Seljuks as they retreated destroyed every farm, burned every fruit tree, and even filled in the wells. Going through the parched land in July sun with very little water or food for men and horse almost did the Crusading army in and not a few men and beast died.

Armenians

Stll there was desert, which proved almost as great an enemy as the Seljuks, until one night camped by the only river there, chanced by some Armenian Christians who for three generations had escaped persecution in their native land; they told the Crusaders that their only hope of survival was to carry with them enormous quantities of water for men and horse.

Edessa

Some Armenians convinced one army of the Crusaders, that under Count Baldwin of Flanders, to come to their city of Edessa,3 and free them from the domination of the Seljuks, hence this army didn't go through the Cicilian Gates as did the others, but by another pass to Edessa. This was the beginning of the first of what would be known as the four Crusader States. This very year (1097) they drove the Seljuks out of Edessa all right, but in time became the masters of the Armenians, replacing their government. But the Armenians didn't seem to mind, because under the Crusaders they prospered more than under their own masters. Enterprising and hardworking Armenians, not just their elite, made much profit from trade under the Crusader easy-going government. (This was not the time, however, when the Armenian Liturgy, which preserved traits of the Liturgy called that of St. James, underwent certain Latinizations; that would come later in Cilicia.)

Cicilian Gates

The remainder (majority) of the Crusaders climbed still higher from the Anatolian plateau into the Tarsus mountains (following the route of Alexander the Great). In places there was but a narrow trail. Imagine a half a million Crusaders going single file on mountain ledges, how long the line must have been, and how many days it would take them all to pass through the Gate. Charles Lamb quotes the Unknown :4

It was so high and narrow that along the path on its flank none of us go ahead of the others. Horses fell into the ravine, and one pack animal would drag over the others. In all quarters the knights showed their misery... asking themselves what they were to do and how they were to manage their arms. Some of them sold their shields and goodly harberks with their helms for three to five dinars, or for anything they could get. They who could not sell their arms cast them away for nothing at all, and marched on."

There were little farms perched on mountain slopes and Armenian villages in the mountains. The Crusaders could not understand their language (except when there were certain Greeks present who knew Armenian) but the Armenians all wore little silver crosses which explained that they were Christian too. The Armenians sold them cheese and milk, bread and meat, and friendly relations began between the Western-rite Christians and the Armenians which became advantageous to both in future years.

As they passed through the Cicilian Gates and saw the fertile plains below, there surfaced a change in policy. Yes, their main objective was Jerusalem, but several of the leaders let it be known that they intended to set up little kingdoms for themselves along the way. This seems like rank cupidity to us today, but as it turned out it was necessary. By now they were 2000 miles and more away from home; money and supplies were running out. Their little kingdoms, begun in avarice became centers of supply and recruitment for the final onslaught on Jerusalem and to hold the Holy Land for some years to come.

1Lamb, Harold, The Crusades, Iron Men and Saints, Doubleday Doran & Co., New York, 1930, pg. 114)

2A plain near the ancient city of that name.

3The ancient stronghold of the Nestorians.

4Lamb, Charles, op. cit., pg. 138. The "Unknown" was a chronicler, surely one of the Crusaders himself, who wrote an account of much of the Crusaders' ventures.

http://www.cathorth....edu/crusd1.html

[ February 26, 2001: Message edited by: MJ ]

#5

Posted 26 February 2001 - 06:49 PM

It had long been apparent that Edessa was vulnerable, but its loss came as a shock to Christians both East and West. Urgent pleas for aid soon reached Europe, and Pope Eugenius III in 1145 issued a formal crusade bull, the first of its kind, with precisely worded provisions designed to protect crusaders' families and property and reflecting contemporary advances in canon law. Legates were designated. The Crusade, energetically supported by Louis VII, was preached by St. Bernard of Clairvaux in France and, with interpreters, even in Germany. As in the First Crusade, many simple noncombatant pilgrims responded. But, since Emperor Conrad III, though at first reluctant to leave Germany, had been won over by Bernard's eloquence, the Second Crusade, unlike the First, was led by two of Europe's major rulers.

The situation in the East was also different. Manuel Comnenus was favourably disposed toward the West and, because of his interest in Antioch, was concerned over the power of Zangi, the Muslim ruler of Aleppo. He was able to assist the crusaders with guides and supplies but contributed no troops. In anticipation of the arrival of the western armies and more aware than they of the delicate power balance in the Levant, he had made peace with the Seljuqs of Iconium in 1146. Above all, Manuel was alarmed by the possibility of an attack by Roger II, the Norman king of Sicily.

Conrad left in May 1147, accompanied by many German nobles, the Kings of Poland and Bohemia, and Frederick of Swabia, his nephew and heir. On leaving Hungary and entering Byzantine territory, he agreed to an oath of noninjury. Conrad's poorly disciplined troops created tension with the Byzantines in Constantinople, where they arrived in September. Both Conrad and Manuel, however, remained on good terms, and both were apprehensive about the moves of Roger of Sicily, who during these same weeks seized Corfu and attacked the Greek mainland.

Conrad, rejecting Manuel's advice to follow the coastal route around Asia Minor, moved his main force past Nicaea directly into Anatolia. On October 25, at Dorylaeum, not far from the place where the first crusaders won their victory, his army, weary and without adequate provisions, was set upon by the Turks and virtually destroyed. Conrad, with a few survivors, retreated to Nicaea.

Meanwhile, about a month behind the Germans, Louis VII, accompanied by his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine, followed the land route across Europe and arrived at Constantinople on October 4. A few of his more hotheaded followers, on hearing that Manuel had made a truce with the Turks of Iconium and totally misunderstanding the motives, accused the Emperor of treason and urged the French king to join Roger in attacking the Byzantine emperor. Louis preferred the opinion of his less volatile advisers and agreed to restore any imperial possessions he might capture.

In November the French reached Nicaea, where they learned of Conrad's defeat. Louis and Conrad then started along the coastal route, the French now in the van, and reached Ephesus. Conrad became seriously ill and returned to Constantinople to the medical ministrations of Manuel. He eventually reached Acre by ship in April 1148.

The French passage from Ephesus to Antioch in midwinter was harrowing in the extreme. Supplies ran short, and the Byzantines were blamed. But Antioch was finally reached in March 1148, and the crusaders were welcomed by Prince Raymond, Queen Eleanor's uncle. Raymond urged an attack on Aleppo, the centre of power of Nureddin, son and successor of Zangi. But King Louis, who resented Eleanor's open espousal of Raymond's project, left abruptly for Jerusalem and forced the Queen to join him.

At Jerusalem, where Conrad had already arrived, a brilliant assembly of French and German notables assembled with Queen Melisend, her son Baldwin III, and the barons of Jerusalem to discuss how best to proceed. Despite the absence of the northern princes and the losses already suffered by the crusaders, it was possible to field an army of nearly 50,000 men, the largest Crusade army so far assembled. After considerable debate, which revealed the conflicting purposes of crusaders and Jerusalem barons, it was decided to attack Damascus.

How the decision was reached is not known. Damascus was undoubtedly a tempting prize, but Unur, the Turkish commander, also fearful of the expanding power of Nureddin and the one Muslim ruler most disposed to cooperate with the Franks, was now forced to seek the aid of his former enemy. And Nureddin was not slow to move toward Damascus. Not only was the campaign mistakenly conceived, it was badly executed. On July 28, after a five-day siege, with Nureddin's forces nearing the city, it became evident that the crusader army was dangerously exposed, and a retreat was ordered. It was a humiliating failure, attributable largely to the conflicting interests of the participants.

Conrad left immediately and stopped at Constantinople, where he agreed to join the Emperor against Roger of Sicily. Louis's reaction was different. His resentment against Manuel, whom he blamed for the failure, was so great that he accepted Roger's offer of ships to take him home and agreed to a plan for a new Crusade against Byzantium. Fortunately the plan was soon abandoned.

The Second Crusade had been promoted with great zeal and had aroused high hopes. Its collapse caused deep dismay, and subsequent expeditions, perhaps wisely, were more limited in their objectives. The Muslims, on the other hand, were enormously encouraged. They had confronted the danger of another major Western expedition and had triumphed over it.

The crusader states to 1187

During the 25 years following the Second Crusade the Kingdom of Jerusalem was governed by two of its ablest rulers, Baldwin III and Amalric I. In 1153 King Baldwin captured Ascalon--the last major conquest of the Franks. The victory extended their coastline southward. But its possession was offset in the next year by the occupation of Damascus by Nureddin, one more stage in the encirclement of the crusader states by a single Muslim power.

In 1160-61 the possibility that the Fatimid caliphate in Egypt, shaken by palace intrigues and assassinations, might collapse and fall under the influence of Muslim Syria caused anxiety in Jerusalem. Thus, in 1164, when Nureddin sent his lieutenant Shirkuh to Egypt accompanied by his own nephew, Saladin, King Amalric decided to intervene. After some manoeuvring, both armies withdrew, as they were to do again three years later.

Meanwhile, Amalric, realizing the necessity of Byzantine cooperation, had sent Archbishop William of Tyre as envoy to Constantinople. But in 1168, before the news of the agreement that William of Tyre had arranged reached Jerusalem, the King set out for Egypt. The reasons are not clear, and there had been considerable division among the barons. At any rate, the venture failed, and Shirkuh entered Cairo. On his death (May 23, 1169), Saladin, then Nureddin's deputy, was left to overcome the remaining opposition and master Egypt.

When the Byzantine fleet and the army finally arrived in 1169, there was some delay, and both armies were forced by inadequate provisions and seasonal rains to retreat once again, each side blaming the other. In 1171, Saladin obeyed Nureddin's order to have the prayers in the mosques mention the Caliph of Baghdad instead of the Caliph of Cairo, who was then in his final illness. Thus ended the Fatimid caliphate and the great division in Levantine Islam from which the Latins had profited.

Ominous developments followed the deaths of both Amalric and Nureddin in 1174. In 1176 the Seljuqs of Iconium defeated the armies of Manuel Comnenus at Myriocephalon. It was a shattering blow reminiscent of Manzikert a century earlier. When Manuel died in 1180, all hope of effective Byzantine-Latin cooperation vanished. Three years later Saladin occupied Aleppo, virtually completing the encirclement of the Latin states. In 1185 he agreed to a truce and left for Egypt.

In Jerusalem, Amalric was succeeded by his son Baldwin IV, a boy of 13 suffering from leprosy. Despite the young king's extraordinary fortitude, his precarious health necessitated occasional regencies and created a problem of succession until his sister Sibyl bore a son, the future Baldwin V, to William of Montferrat. Her marriage in 1180 to Guy of Lusignan, a newcomer to the East and brother of Amalric, the constable, accentuated existing rivalries among the barons. A kind of "court party" centring around the queen mother, Agnes of Courtenay, her daughter Sibyl, and Agnes' brother, Joscelin III, and now including the Lusignans was often opposed by another group composed mostly of the so-called native barons--old families, notably the Ibelins, Reginald of Sidon, and Raymond III of Tripoli, who through his wife was also lord of Tiberias. In addition to these internal problems, the kingdom was more isolated than ever. Urgent appeals to the West and the efforts of Pope Alexander III had brought little response.

Baldwin IV died in March 1185, leaving, according to previous agreement, Raymond of Tripoli as regent for the child king Baldwin V. But when Baldwin V died in 1186 the court party outmanoeuvred the other barons and, disregarding succession arrangements that had been formally drawn up, hastily crowned Sibyl. She in turn crowned her husband, Guy of Lusignan.

In the midst of near civil war, Reginald of Châtillon, lord of Kerak and Montréal, broke the truce by attacking a caravan. Saladin replied by proclaiming jihad against the Latin kingdom. In 1187 Saladin left Egypt, crossed the Jordan south of the Sea of Galilee, and took up a position near the riverbank. Near Saffuriyah (modern Zippori) the crusaders mobilized an army of perhaps 20,000 men and including some 1,200 heavily armed cavalry, probably the equal of Saladin's. In a spot well chosen and adequately supplied with water and provisions, they awaited Saladin's first move.

On July 2 Saladin blocked the main road to Tiberias and sent a small force to attack the town, hoping, since Count Raymond's wife was there, to lure the crusaders into the open. Nevertheless, it was Raymond who at first persuaded the King not to fall into the trap. But, late that night, others, accusing the Count of treason, prevailed upon the King to change his mind. It was a fateful decision. For, after an exhausting day's march on July 3, a terrible night spent without water, surrounded and constantly harassed, and a long day of fighting near the Horns of Hattin on July 4 with smoke from grass fires set by the enemy pouring into their faces, the foot soldiers broke and fled, destroying the essential coordination with the cavalry. When Saladin's final charge ended the battle, most of the knights had been slain or captured. Only Raymond of Tripoli, Reginald of Sidon, Balian of Ibelin, and a few others escaped.

The King's life was spared, but Saladin killed Reginald of Châtillon and ordered the execution of some 200 Templars and Hospitallers. Other captive knights were treated honourably, and most were later ransomed. Less fortunate were the foot soldiers, most of whom were sold into slavery. Virtually the entire military force of the Kingdom of Jerusalem had been destroyed.

Saladin quickly followed up his victory at Hattin. Pausing only to take Tiberias, he moved toward the coast and seized Acre. By September 1187 he and his lieutenants had occupied most of the major strongholds in the kingdom and all of the ports south of Tripoli, except Tyre, and Jubayl and Botron (al-Batrun) in the County of Tripoli. On October 2, Jerusalem, then defended by only a handful of men under the command of Balian of Ibelin, capitulated to Saladin, who agreed to allow the inhabitants to leave after paying a ransom. Though Saladin offered to release the poor for a specified sum, several thousand apparently were not redeemed and probably were sold into slavery. In Jerusalem, as in most of the cities captured, those who elected to remain were Syrian or Greek Christians. Somewhat later Saladin permitted a number of Jews to settle in the city.

Meanwhile, Saladin continued his conquests in the north, and by 1189 all the kingdom was in his hands except Belvoir (modern Kokhov ha-Yarden) and Tyre. The County of Tripoli and the Principality of Antioch were each reduced to the capital city and a few outposts. The larger part of the 100-year-old Latin establishment in the Levant had been lost.

The institutions of the First Kingdom

The four principalities established by the crusaders--three after the loss of Edessa in 1144--were loosely connected, and such limited suzerainty as the king of Jerusalem exercised over the others became largely nominal after the midcentury. Each of the states was organized into a pattern of feudal lordships by the ruling minority. The institutions of the Kingdom of Jerusalem are best known, partly because its history figures more prominently in both Arab and Christian chronicles but especially because its documents were better preserved. In the 13th century there was compiled a collection of laws, the famous Assises de Jérusalem. Though this collection reflects a later situation, certain sections and many individual enactments can be traced back to the 12th century, the period known as the First Kingdom.

In the first half of the 12th century the kingdom presented the appearance of a typical feudal monarchy on the European model, with lordships owing military service and subject to fiscal exactions. There were, however, important differences, not only in the large subject population of diverse ethnic origins but also with respect to the governing minority. No great families with extensive domains emerged in the early years. Further, the typical noble's residence was not, as in Europe, the rural castle or manor house. Castles there were, but they were garrisoned by knights and, increasingly as the century advanced, by the religio-military orders. But most Jerusalem barons lived in the fortified towns. The kings, moreover, possessed a considerable domain and retained extensive judicial rights. As a consequence, the monarchy was a relatively strong institution in early Jerusalem.

Toward the middle of the century this situation began to change. Partly as a consequence of increased immigration from the west, the baronial class grew, and there was formed a relatively small group of magnates with large domains. As individuals, they were less disposed to brook royal interference, and as a class and in the court of barons (Haute Cour, or High Court) they were capable of presenting a formidable challenge to royal authority. The last of the kings of Jerusalem to exercise effective power was Amalric I in the 12th century. In the final years of the First Kingdom, baronial influence was increasingly evident and dissension among the barons, as a consequence, more serious.

The military orders

Another serious obstacle to the king's jurisdiction and one not found, at least in the same form, in the West was the extensive authority of the two religio-military orders. The older of the two, the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, or Hospitallers, was founded in the 11th century by the merchants of Amalfi to provide hospital care for pilgrims. The order never abandoned its original purpose, and, in fact, as its superb collection of documents reveals, the order's philanthropic activities expanded. But during the 12th century, in response to the military needs of the kingdom, the Hospitallers followed the example of the Templars and became, in addition, an order of knights.

The Poor Knights of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, so called because of their headquarters in the former temple of Solomon, originated as a monastic-military organization to protect pilgrims on the way to Jerusalem. Its rule, composed by St. Bernard of Clairvaux, was officially sanctioned by the Council of Troyes (1128). Although Templars and Hospitallers took monastic vows, their principal function was soldiering.

The orders grew rapidly, and, as they acquired castles at strategic points in the kingdom and in the northern states and maintained permanent garrisons, they supplemented the otherwise not entirely adequate forces of the barons and king. Moreover, since they were soon established in Europe as well, they became international in character. Virtually independent, sanctioned and constantly supported by the papacy, and exempt from local ecclesiastical jurisdiction, they aroused the jealousy of the clergy and constituted a serious challenge to royal authority.

The crusaders introduced into the conquered lands a Latin ecclesiastical organization and hierarchy. The Greek patriarch of Antioch was, as has been mentioned, removed, and all the subsequent incumbents were Latin, except for one brief period before 1170, when imperial pressure succeeded in installing a Greek. In Jerusalem the Orthodox patriarch had left before the conquest and died soon after. All his successors were Latin.

Under the Latin jurisdiction was the entire Latin population and those natives (Greek in Antioch and Greek or native Syrian [Melchite] in Jerusalem) who had remained Orthodox. Outside was a larger number of Monophysites (Jacobite or Armenian) and some few Nestorians, all adherents of doctrines that had deviated from the decisions of 5th-century ecumenical councils. A number of Maronites of the Lebanon region accepted the Latin obedience late in the 12th century. After some initial confusion, the native hierarchies were able to resume their functions.

As in the West, the church had its own courts and possessed large properties. But each ecclesiastical domain was required to furnish soldiers, and the charitable foundations were considerable. The hierarchy of the Latin states was an integral part of the church of the West. Papal legates regularly visited the East, and bishops from the crusader states attended the Third Lateran Council in 1179. Western monastic orders also appeared in the crusader's states.

In addition to the nobles and their families who had settled in the kingdom, a substantially larger number of persons was classified as bourgeois. A small number had arrived with the First Crusade, but most were later immigrants from Europe, representing nearly every nationality, but predominantly from rural southern France. In the East they became town dwellers, but a few were agriculturalists, proprietors of small estates, rarely themselves tillers of the soil, inhabiting the more modest towns. Some immigrants, it appears, perhaps poor pilgrims who remained, failed to obtain a reasonably settled status and could not afford the relatively small ransom offered by Saladin in 1187.

The townsmen of the First Kingdom did not, like their counterparts in Europe, aspire to political autonomy. There were no communal movements in the 12th century. The bourgeois were, therefore, subject to king or seigneur. Some did military service as sergeants; i.e., mounted auxiliaries or foot soldiers. Bourgeois were recognized as a class in the more than 30 "courts of the bourgeois" according to procedures laid down in the Assises de la cour des bourgeois, which, unlike other parts of the Assises, reflects the traditions of Roman law in southern France.

The Italians, because they supplied indispensable naval aid and shipping essential to regular contact with Europe, had been able to acquire exceptional privileges in the ports. These privileges usually included a quarter that they maintained as a virtually independent enclave. Its status guaranteed by treaty between the kingdom and the mother city (Venice, Genoa, Pisa, etc.), the Italian enclave more nearly resembled the modern overseas colony than any other establishment of the crusaders.

The European settlers in the crusader states constituted only a small minority of the population. If the early crusaders were ruthless, their successors, except for occasional outbursts during campaigns, acquired not only a remarkable tolerance but also a notable flexibility in dealing with the diverse sectors of the native population. Those Muslim town dwellers who had not fled were captured and put to menial tasks. Some, it is true, appeared in Italian slave marts, but royal and ecclesiastical ordinances at least laid down limits to what slave owners might do. Baptism brought with it immediate freedom.

Not all Muslims were slaves. Most of those who remained were peasants who for centuries had constituted a large part of the rural population and who were permitted to retain their holdings, subject to fiscal impositions not unlike those of the European serf, and usually identical with those originally levied by their former proprietors on all non-Muslims. Muslim nomads, or Bedouins, who from time immemorial had moved with their herds as changing seasons provided pasturage, continued to enjoy pasturage rights within the kingdom guaranteed by the king.

Most mosques were appropriated during the conquest, but some were restored, and no attempt was made to restrict Muslim religious observance. Occasionally a mihrab (prayer niche) was retained for Muslim worshippers in a church that had formerly been a mosque. The tolerance of the Franks, noted by Arab visitors, often surprised and disturbed newcomers from the West.

Legal practices

Native Christians, predominantly townsmen, were governed according to the Assises de la cour des bourgeois. Each national group retained its institutions. The Syrians, for example, maintained a cour du rais, the rais (ra'is) being a chieftain and often of importance under the Frankish regime. An important element in the kingdom's army, the corps of Turcopoles, lightly armed cavalry units, was also composed largely of native Christians, including, apparently, converts from Islam. The principle of personality of law applied to all. The Jew took oath on the Torah, the Samaritan on the Pentateuch, the Muslim on the Qur'an, and the Christian on the Gospels.

The Jewish community of Palestine, which had already begun to diminish in the 11th century, was drastically reduced by the First Crusade. But gradually, as the Latin kingdom settled into a routine of government, the situation improved. Indeed, there is reason to believe that the later, more stable regime made possible a not inconsiderable Jewish immigration, not, it seems, as in earlier times, from the neighbouring lands of the Middle East, but from Europe.

Thus, by the 1170s the crusader states of Outremer, as the area of Latin settlement came to be called, had developed well-established governments. With allowance made for regional differences (e.g., Antioch in its early years under the Norman dynasty was somewhat more centralized), the institutions of the northern states resembled those of Jerusalem. The governing class of Franks was no longer made up of conquerors from abroad but of local residents who had learned to adjust themselves to a new environment and were concerned with administration. A few--as, for example, Reginald of Sidon and William of Tyre, archbishop and chancellor--were fluent in Arabic. Many others knew enough of the language to deal with natives. Franks adopted native dress, ate native food, employed native physicians, and married Syrian, Armenian, or convert-Muslim women.

But the Franks of Outremer, though they sometimes acquired a love of luxury and comfort, did not lose the will or ability to confront danger; nor did they "go native." In fundamentals, they continued to adhere to the traditions of their French forebears. They were Latin Christians. Documents were drawn up in Latin. The Assises were in French. William of Tyre, born in the East but educated in Europe, wrote a celebrated History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea in the Latin style of the 12th century.

Artists and architects were influenced by Byzantine and Arab craftsmen, but Oriental motifs are usually limited to details, such as doorway carvings. A psalter for Queen Melisend in the 12th century, for example, shows certain Byzantine characteristics, and the artist may have lived in Constantinople, but the manuscript is in the current tradition of French art. Castles followed Byzantine models, often built on the old foundations, but Western ideas were also incorporated. New churches were built or additions made to existing structures, as for example the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, in the Romanesque style of the homeland.

All in all, the Franks of the First Kingdom were developing a distinctive culture and achieving a sense of identity. Until baronial dissensions weakened the monarchy in later years--a human failing, not a deep cultural maladjustment--the Latin kingdom showed remarkable vitality and ingenuity. It was one of the more sophisticated governmental achievements of the Middle Ages.

http://www.britannic... 110241,00.html

[ February 26, 2001: Message edited by: MJ ]

#6

Posted 27 June 2001 - 06:44 AM

Another aspect of the Crusading period that deserves a mention is the Mongol Invasion of the early 13th century. It may have been mentioned in your posts, but on skimming them, I didnt notice anything.

Anyways the Mongols invaded during the reign of Ogedei Khan and the general who led the invasion was a Christian convert (there were many Christian and Muslim converts among the Mongols, but most didnt take religion seriously either way), I forget his name. To the Armenians this was a new hope as the Europeans were no longer interested in the Middle East. The Armenian King at the time (whose name also illudes me at this moment) signed a secret alliance with the Mongol Emperor in the Mongol capital in the East. Anyways to make a long story short, the Armenians and their new aliies proceded to raising the Muslim cities in the area, north of Palestine. One of these happened to be Baghdad, at the time a prospering Muslim urban center. The rampage continued for a number of years until Ogedei suddenly died and the Mongols halted their advance in anticipation of what was to take place at home. Meanwhile a Mongol advance army was desicivelly defeated at Ain Yalut by a much larger force of the Mamluks of Egypt. If Ogedei had not died, the Mongols would have surelly taken Egypt also (the last major Muslim power of that time), and the Middle East may have been an altogether a different place.

some food for though.

Cheers.

#7

Posted 27 September 2003 - 02:35 PM

#8

Posted 27 September 2003 - 03:45 PM

The destruction of the Bagratid Kingdom was completed by raids of new savage invaders, the Seljuk Turks from Central Asia. These 'people' virtually destroyed almost all of Armenian & Greek culture in the region. With little resistance from weakened Byzantium, the Seljuk Turks spread into the Armenian highlands as well as Eastern Europe. This invasion compelled a large number of Armenians to move south, toward the Taurus Mountains close to the Mediterranean Sea, where in 1080 they founded, under the leadership of Ruben (Rubenid/Rubinian dynasty), the Kingdom of Cilicia. Close contacts with the Crusaders and with fellow Europeans led to the creation of a new European state, absorbing feudal class structure. Cilician Armenia became a country of barons, knights and serfs. The court at Sis adopted European clothes. Latin and French were used alongside Armenian.The close relationship with Western European countries played a very important role during the Crusades. Cilicia provided the Christian armies a safe haven and provision on their way towards Jerusalem. Intermarriage with European crusading families was common, and Western European religious, political, and cultural influence was strong. Many Latin terms entered the Armenian language. Cilician Armenia also played an important role in the trade of the Venetians and Genoese with the East. The Cilician period is regarded as the Golden Age of Armenian Illumination, noted for the lavishness of its decoration and the frequent influence of contemporary Western manuscript painting. Their location on the Mediterranean coast soon involved Cilician Armenians in international trade between the interior of Eurasia and Europe. Enduring constant attacks by the Turks, Mongols and Mamelukes, Cilician Armenia survived for three centuries and fell to Egyptian Mameluks in 1375. The last Armenian king of Cilicia, Levon VI Lousinian, emigrated to France, where his grave still can be seen in the St. Denis Cathedral of Paris. The title "King of Armenia" passed to the kings of Cyprus, then to the Venetians, and was later claimed by the house of Savoy.

The Crusades & Cilicia

1096-1102 - The First Crusade: Bagrat contacts the crusading forces at Nicaea and accompanies them across Asia Minor. He forms an alliance with Baldwin of Boulogne. The Franks enter parts of Cilicia but their hold is insecure because of Byzantine invasions and the objections of the native Armenian princes who get the upper hand in the late 1130s. Byzantine takes over Cilicia followed by seven years of relative peace ruled by Byzantium. On April 8th, 1143 John Comnenus Emperor of Byzantine dies as a result of a poisoned arrow. The Second Crusades begin in 1147. Rubenid family allies and marries Franks and fights the Turks and Byzantines together. Hromkla is given to the Armenian catholicos by Beatrice Princess Of Lorraine. In 1179 a religious synod is held at Hromkla to discuss the celebration of Christmas on December 25, instead of the Armenian custom of combining it with the Epiphany on January 6; the method for choosing the date of Easter; the use of fermented bread at mass; and changes in the church services. Emperor Manuel Comneus dies in 1180. In 1189 the Third Crusades begin. Note: Armenian Kings Leon/Levon are numbered differently by various historians, it's easier to understand who is who by the dates instead of I, II etc. Leon sends Nerses of Lampron as ambassador to meet Emperor Frederick Barbarossa when he approaches Cilicia, but on June 10 Barbarossa drowns in the Saleph River near Silifke, ending negotiations for Levon's royal crown. Catholicos Grigor Tgha dies and his nephews, Hetoum and Shahnshah, are assassinated. Gregory V is elected as the new catholicos but doesn't get along with Levon and is imprisoned later killed while trying to escape. On January 6, 1198 Levon/Leon I is crowned as King of Lesser Armenia (Cilicia) by the new Armenian catholicos with a crown from the Hohenstaufen emperor. In return, he is forced to recognize the German emperor as his lord and the pope in Rome as the head of the Armenian Church. The Armenian church however stalls and does not change or adopt the Roman Catholic forms of worship. Constantinople is sacked by crusaders of the Fourth Crusade(1202-1204). Catholicos John of Sis accuses Isabelle of Austria, Levon's queen and mother of his daughter Rita, of adultery and she is imprisoned at Vahka where she died. King Levon of Cilicia marries Sybilla of Lusignan, the daughter of King Aimery of Cyprus and Queen Isabeau Plantagenet, and later mother of Levon's daughter and heir Isabelle (Zabel). Levon's wife's sister, Helvis marries to Raymond-Roupen of Antioch. Two years after the start of the Fifth Crusades, King Levon dies in 1219 reigning 32 years. Isabelle becomes queen, Adam of Baghras the regent. Phillip the son of Raymond count of Tripoly marries Isabelle in 1222. He is later imprisoned and killed in the fortress of Sis. King Levon I's daughter Isabelle is forced to marry Hetoum I (or Hetum I) which joined the Rubenid and Hetumian families. Isabelle runs away from her forced marriage to Hetoum, but eventually reconciles to it. Seljuk Turk animals invade other neighbouring Armenian kingdoms next to Cilicia. Genghis Khan later shatters the Seljuk grip on the region. King Hetoum I (or Hetum I) goes to visit the Genghis Khan for three years and comes back through Greater Armenia, the homeland no Cilician ruler had previously been able to visit. He acquires guarantees that the Mongol savages will protect the Christian Churches in their conquered lands. Bohemond VI of Tripoli marries Hetoum's daughter, Sybille and Prince Levon is knighted at Mamistra. Prince Constantine follows his father as lord of the fortress of Servandikar which dominates the main roads to Cilicia from the east and at Sis he marries King Hetoum's daughter Rita. Prince Levon of Cilicia marries Keran, daughter of Hetum of Lambron. Keran and two of their children died of the plague that struck Europe after 1272 and before Hetoum's death in 1270. Baybars, Mamluk leader, takes Syria, Caesarea, Haifa, Arsuf, Tibnin, and Safad and then turns on Europe. King Hetoum goes to the Mongols for help and while he is gone Princes Levon and Thoros are imprisoned in Cairo and the Mamluks sack Sis, Mamistra, Adana, Ayas, and Tarsus. On May 12, 1268 the Mamluks take Antioch and massacre the inhabitants. Hetum gets his son released from Egypt, abdicates in Levon's favor, and enters a monastery. King Hetum I; father of Fimi (Countess of Sidon) and Levon (crown prince); brother of Bishop Johannes dies in 1270. Marco Polo sets out for Cathay from the Armenian port of Ayas in 1271, not long after the Mamluks try again to conquer Europe through Cilicia. General Smbat, Levon's uncle, traps Mamluk troops in a mountain pass and wins a major battle. Smbat and 300 knights die in the battle. Hetum II abdicates in favor of his brother Thoros (who was strangled by their brother Smbat). Hetum retires to a Franciscan monastery and resumes the throne in 1294. Temporary allied Mongols and Armenian Knights with various other European Knights fight the Mamluks at Homs and win, regaining all their Cilician property. In 1304, The Grand Khan, nicknamed Gazan (which means savage), declares Islam the official religion in his lands and later his son orders all Christians throughout his lands to wear a black linen strip over the shoulder. Hetum II and his nephew, now King Leon, are murdered by the savage Mongols (now even more animalistic under Islam) Anavarza with all their followers. Oshin, Hetum's brother, chases the Mongol troops out. Oshin is poisoned Young Levon is forced to marry his regent's (Oshin of Corycus) daughter, Alice. King Levon in 1329, aged nineteen, takes charge of the kingdom and has his unfaithful wife and her father both killed. King Levon marries Constance Eleanor of Aragon, daughter of Frederick II of Sicily and widow of Henry II of Cyprus. Mamluks attack and take the Cilician port city of Ayas. King Leon V, stays in the citadel of Sis instead of fighting the Mamluks, waits for Western European help, the dissapointed barons murder him in 1341. The following year, barons offer the crown to John of Lusignan who offers the Cilician crown to his brother Guy. Guy agrees and comes to Cilicia. He brings Western European influence to the monarchy and encourages union with the Roman Church. Guy Lusignan sends his younger brother, Bemon, to the Pope in Avignon, France for help; but the negotiations rouse resentment in the barons. Guy, Bemon and their bodyguards are murdered. Constantine III, son of Marshall Baldwin of Neghr, is elected king. He marries Marie, daughter of Oshin (a former regent) and Jeanne of Anjou. Peter I of Cyprus gets the port castles of Korykos in Cilicia in return for helping Constantine VI against the Karamanids Constantine III dies of natural causes and Constantine IV becomes king of Cilicia and marries Marie widow of Constantine III in 1363. Peter of Cyprus is murdered by the Muslims so Constantine VI makes a treaty with the sultan of Cairo, the barons are not very happy that Constantine signed a treaty with non-Europeans. Queen Marie sends Pope Gregory XI a letter requesting military help against the Muslims. Constantine is murdered, and the Pope wants Marie to marry Othon of Brunswick. Leon, son of John of Lusignan and Soldane, is invited by the barons to become king. (Soldane, daughter of King Georgi VII of Georgia, may have been John of Lusignan's mistress and not his wife, and her sons may or may not have been legitimate. Levon's claims to his grandmother Isabella's estates were rejected on those grounds by the Pope.) Levon, delayed in Cyprus on his wife's lands, is "taxed" by the Genoese 280 livres of gold plus 300 ducats ransom for his crown, silver plate, and clothing. His wife's lands are forfeited to Catherine of Aragon. Levon is forced to sell his personal possessions to travel and hire troops. In 1374, Levon VI, a Roman Catholic, and his wife, Margaret of Soissons, are crowned at Sis on September 14 in both an Armenian and Latin ceremony. To their surprise they discover an empty treasury. Next year on January 15 the Mamluks of Egypt capture parts of Sis. February 24, the rest of Sis is evacuated and burned by Levon and his supporters. April 13, Levon VI, his wife, and their twin baby daughters surrender to the Mamluks. July, Levon is taken to Cairo as a captive where he is released from jail, constantly watched by the Arabs and given a daily pension of 60 dirhems. Levon's wife, Marguerite de Soissons, and daughters die in Cairo. In 1382, Levon is ransomed using money from the Kings of Castile and Aragon, 300 squirrel pelts, a gold and silver cup, and a gilded jar. In 1386 Levon serves as an envoy to King Richard II of England. November 29, King Levon VI (John de Lusignan) dies. He is interred with French Royalty in the Basilica of St. Denis. He was in France for help to regain Cilicia. His son Guyot becomes a military man and Philippe becomes an archdecon. The Tartar barbarians invade Asia Minor in 1402. Forty years later the seat of the Armenian Catholicos is moved from Sis to Etchmiadzin. 1453, the Ottoman savages capture Constantinople. 1605, after burning and destroying what they could in the former area of eastern Greater Armenia, the Persians require their Armenian subjects to move to New Julfa and away from the invading Turkish troops. Many Armenians escape north to the Eastern European states such as Poland. 1620, the Persian rule of Eastern Armenia begins...

#9

Posted 30 October 2004 - 04:57 PM

Crusade for Jerusalem 1095-1100

Jerusalem Kingdom of the Baldwins 1100-1131

Crusaders, Manuel, and Nur-ad-Din 1131-1174

Saladin and Crusading Kings 1174-1198

Crusades to Constantinople and Egypt 1198-1255

Mongol and Egyptian Invasions 1255-1300

Crusade for Jerusalem 1095-1100

After the Byzantine empire suffered a major defeat in 1071, fear of continuing Seljuk conquests stimulated Byzantine emperors to write to the West for military help. Pope Gregory VII considered leading a crusade himself but his reforms brought him into serious conflict with Germany's Heinrich IV, whom he had wanted to protect the Church while he was gone. Normans led by Robert Guiscard had tried to overcome the Byzantine empire militarily and had failed. After defeating the Norman threat, Emperor Alexius Comnenus again asked the West for assistance.

At the Council of Clermont in November 1095 Pope Urban II met with about 300 clerics and described the plight of the Byzantines facing the Seljuk Turks and the suffering of pilgrims going to Jerusalem. He proposed that the rich and poor go to save the East, and he promised remission of the penance for sins, absolution, and protection of their property by the Church while they are gone. Shouts of "God wills it!" erupted, and the Bishop of Le Puy was the first to kneel down and volunteer. Each crusader should wear the sign of the cross and vow to go to Jerusalem. Any taking the vow who failed to set out or turned back were to be excommunicated. Clerics and monks must get permission of their bishop or abbot. The elderly and weak were discouraged from attempting the challenging adventure. This crusade was not intended to be a war of conquest, as all Eastern churches recovered were to have their rights restored. The plan was to leave following the harvest the next summer and to assemble at Constantinople. The crusade was intended to supplement the Truce of God, which the Clermont council endorsed, by removing warriors from Europe. Floods and pestilence had ravaged Europe in 1094, followed by drought and famine in 1095. Urban had argued at Clermont that they were fighting among themselves, because they could not feed people. Prophets argued that the Christ would not come again until the Holy Land had been recovered.

Adhémar de Monteil, Bishop of Le Puy, was elected the leader, and Count Raymond of Toulouse soon joined. In his travels Pope Urban preached the crusade at Limoges, Tours, Toulouse, and Nimes. Urban wrote to Flanders, and Genoa offered twelve galleys for transport. Adhémar and Raymond were joined by Hugh of Vermandois, Robert II of Flanders, Duke Robert of Normandy, Count Stephen of Blois, Duke Godfrey of Lower Lorraine, Count Eustace III of Boulogne, and his brother Baldwin. Normans from Italy were led by Guiscard's son Bohemond. Pope Urban commissioned Robert Arbrissel to preach the crusade in the Loire valley; but the greatest inspirer was a monk called Peter the Hermit, who wandered around barefoot and on a donkey. Peter already had a following of those devoted to helping the poor as he had traveled around the Ile de France, Normandy, Champagne, and Picardy for years. Peter also converted nobles and the wealthy, who contributed some or even all of their possessions so that his ascetic community had its own resources for its charitable work. Peter had provided many dowries to prostitutes so that they could reform their lives. Peter began preaching the crusade, and his following quickly grew as he moved through the French provinces. He obtained a letter from the chief rabbi at Rouen to the Jews of Mainz, urging them to contribute.

Byzantines had expected a few mercenary soldiers to cross the Adriatic Sea and travel through Thessalonica when suddenly they learned that massive armies had come by way of Hungary and had arrived in their empire at Belgrade. The Byzantine empire had just suffered a plague of locusts, which ate the vines but left the grain. Some interpreted this to mean the crusaders would kill the Saracens and protect the Christians; but the Byzantines were not so sure. According to the history of his daughter Anna Comnena, Emperor Alexius believed that the Franks' greed for money caused them to break their agreements.

Proud Franks composed the first group led by Walter Sans-Avoir. They were ridiculed by Germans at first but had money to buy food as they passed through Hungary. Sixteen stragglers crossing a river at Semlin had been robbed of their weapons and clothes, which were displayed on the wall as a warning to other crusaders. Unable to buy food, Walter's crusaders foraged, and sixty were burned to death in a church. Walter quickly moved his band on to Nish, where they could buy provisions. Byzantine officials came there to escort them to Constantinople, where they arrived in mid-July 1096.

Peter's preaching in Germany increased this largest group of crusaders to at least 20,000 and maybe 40,000. He promised Hungary king Coloman his people would not pillage or fight in the markets. At Semlin a quarrel over a sale of shoes escalated into a riot and a battle, as Geoffrey Burel led an attack on the town that killed 4,000 Hungarians. Belgrade was not expecting them, and the Byzantine governor of the Bulgarian province, Nicetas, evacuated the city. Pechenegs keeping imperial order tried to restrict crossing the Save River to one place and were attacked by Peter's crusaders, who captured and put some Pechenegs to death. Crusaders pillaged Belgrade and set it on fire. At Nish Peter asked Nicetas for food; but he required Peter to give him Walter of Breteuil and Geoffrey Burel as hostages for their good behavior. Some incidents did occur, and the baggage train in the rear was attacked, capturing some crusaders and pilgrims, who may have spent the rest of their lives as slaves. When Peter gathered his band, one witness estimated a quarter had been lost. At Sofia Byzantine officials promised them free markets the rest of the way through Philippopolis and Adrianople, and Peter's band arrived safely at Constantinople on August 1, 1096.

Some of the popular armies that formed in Germany were not as well led. The need for money exacerbated the resentment that had built up against Jewish money-lenders, who were not inhibited by the Christian condemnation of usury. Jews in Mainz and Cologne offered five hundred silver coins to Godfrey, Duke of Lower Lorraine, and King Heinrich IV urged the protection of Jews. However, an ambitious robber baron named Emich of Leisingen led a gang that murdered twelve Jews in Spier before the bishop stopped them by cutting off the hands of several murderers. At Worms Emich's men overcame the bishop and slaughtered about 500 Jews in his palace. Mainz closed its gates; but Emich took seven pounds of gold from a Jew and then attacked the archbishop's palace. Only a few Jews, who renounced their faith, were saved from the massacre of about a thousand, and some of the apostates later committed suicide. Anti-Jewish riots had already occurred in Cologne, and the Jews hid except two who died when the synagogue was burned. Most Jews in Trier were protected in the palace of the archbishop, but in Metz and other cities the persecutors killed more in June 1096.

Volkmar's soldiers attacked and massacred the Jewish community in Prague, as religious hatred became an excuse for plundering. A small group with German priest Gottschalk killed Jews at Ratisbon; after foraging and robbing Christians in Hungary, they were eventually surrounded by Hungarian troops and massacred. Hungary's king Coloman refused to let Emich and his men cross the river to Wiesselburg. After six weeks of skirmishing by the bridge, the Germans built another bridge; but in a battle the crusaders were defeated, though Emich and other knights escaped on horses. A group led by Godfrey of Bouillon also took the northern route, and he had to give his brother Baldwin and his family as hostages to pass safely through Coloman's Hungary. Godfrey announced that any violence would be punished with death.

Peter's crusaders were conveyed across the Bosphorus to Asia, where the Germans and Italians quarreled with the French and elected Rainald as their leader. Both groups stayed near the coast as they traveled and raided the countryside, where Christians lived. From Civetot the Franks led by Geoffrey Burel headed south and approached Nicomedia, the capital of Seljuk sultan Kilij Arslan, son of Suleiman. Anna Comnena reported that they sacked villages and massacred Christians, even their babies. A Turkish force was driven off, and they returned to Civetot with their booty. This aroused 6,000 Germans, and Rainulf led them to capture the castle Xerigordon though they avoided killing Christians. A Turkish army survived an ambush and withheld their water supply for eight days until Rainulf surrendered. Only those who renounced Christianity were spared, while the others were enslaved. Peter had gone back to Constantinople to get aid from the Emperor. In October 1096 the entire army of 20,000 crusaders marched toward Nicaea and was ambushed by the Turks. Most of the crusaders' leaders were killed or seriously wounded, as the army panicked and fled. About 3,000 managed to take refuge in an old castle and held out; but all the rest were slaughtered by the Turks. Emperor Alexius sent warships, and the Turks lifted the siege of the castle.

Hugh of Vermandois was the brother of Frank king Philip, and his band was so small after sailing across the Adriatic that they were escorted by imperial officials to Constantinople. When Godfrey heard that Hugh of Vermandois was being held by Emperor Alexius, he allowed his men to forage in Byzantine territory. Normans led by Bohemond knew the route from Dyrrhachium, and in January 1097 they destroyed a village because it was inhabited by heretic Paulicians. Bohemond won the gratitude of local citizens after he restrained young Tancred from looting, though after Bohemond went ahead, Tancred's men resumed foraging. Alexius feared most the ambition of the Norman Bohemond, whom he had previously defeated, and he refused to appoint him the crusaders' commander. Count Raymond of Toulouse and Bishop Adhémar of Le Puy led the largest real army and marched by land through northern Italy. Adhémar was wounded by Pecheneg mercenaries. After an ambush these crusaders attacked Byzantine troops; but a letter from Emperor Alexius calmed things down. The refined Raymond was the crusader most admired by Alexius and his daughter Anna, and he was allowed to make a modified oath that he would serve under the Emperor if he chose to lead the Christian forces.

Hugh of Vermandois swore allegiance to Emperor Alexius and persuaded most other crusaders to do so; but Godfrey held back. When Alexius shut off his supplies, Baldwin raided the suburbs until Alexius ended the blockade. Alexius wanted these crusaders to move on, because more were coming; so in March 1097 he began reducing supplies of horse fodder, fish, and then bread. Crusaders raided the villages and fought with the Pecheneg police. Baldwin's men captured and put to death sixty Pechenegs. During holy week Godfrey attacked Constantinople, and according to Anna, Emperor Alexius ordered his forces to shoot arrows but not kill their fellow Christians. Finally he sent in his imperial guards, and the crusaders fled. Godfrey acknowledged the Emperor as overlord of any Byzantine territory they might reconquer, and his army was transported across to Asia. The fourth great crusading army was led by Duke Robert of Normandy and did not arrive in Constantinople until May 1097. The total number of crusaders was estimated by the chroniclers at 600,000 by Fulcher of Chartres, 300,000 by Ekkehard, and 100,000 by Raymond of Aguilers; but modern scholars believe there were probably about 7,000 knights and about 60,000 infantry.

Greek engineers led by Manuel Butumites joined the crusaders, who made decisions by a council of their leaders. The armies of the crusaders surrounded the walls of Nicaea before a relieving Turkish force arrived. The Sultan's army attacked Raymond's forces on the south side and after a day's battle retreated, wounding almost all the crusaders they encountered. Nicaea still gained supplies by the lake until Emperor Alexius sent Byzantine ships that enabled Manuel Butumites to win their surrender before the crusaders attacked. Alexius ordered a gift of food to every crusader, and shared the ample treasure taken with the leaders, though Tancred demanded a larger portion and delayed giving the homage all the other crusading leaders pledged. The crusaders were surprised that the Emperor allowed the Turkish captives to buy their freedom, and Alexius even returned the Sultan's daughter without ransom. A small detachment of Byzantine troops led by Taticius joined the crusaders as they marched to Dorylaeum. The crusaders marched in two armies a day apart, and the first army led by the Normans was attacked by Turks and surrounded; but the second army arrived at mid-day, causing the Turks to flee to the east and leave their camp and treasure behind as they ravaged the country to make it hard for the crusaders.

A Turkish army led by two governors (emirs) in Cappadocia also fled when they were attacked at Heraclea. The crusaders found Caesarea deserted, but they kept their agreement by establishing Byzantine governors there and in Placentia, Marash, Artah, and other places. Meanwhile Emperor Alexius sent a force led by his brother-in-law Caesar John Ducas to fortify Nicaea and to reconquer Ionia and Phrygia. The emir of Smyrna surrendered and was allowed to withdraw to the east. After taking Ephesus the army of John Ducas captured the Lydian cities of Sardis, Philadelphia, and Laodicea in the fall of 1097.

Both Godfrey's younger brother Baldwin and Bohemond's nephew Tancred were younger sons without property and wanted to find a place to rule. Tancred led about 300 soldiers and besieged Tarsus, the chief city of Cilicia. Tancred sent for help, but Christians opened the gates before Baldwin's army arrived. Tancred reluctantly transferred authority to Baldwin and departed. When 300 Normans arrived to relieve Tancred, Baldwin would not let them in the gates, and they were massacred at night by the former Turkish garrison. Other crusaders blamed Baldwin for this. Turks fled as Tancred took Adana and Mamistra. When Baldwin's forces arrived, Norman prince Richard persuaded Tancred to punish Baldwin with a surprise attack; but they had to retreat, and Baldwin and Tancred were reconciled.

Baldwin learned that his wife and children had died of illness. Advised by Bagrat, Baldwin gained the support of the Armenian Christians as Turkish garrisons either fled or were massacred. Baldwin conquered as far as the Euphrates by taking Ravendel and Turbessel. The Armenian Bagrat was suspected, tortured, and escaped to the hills. At Edessa Baldwin was adopted as the son of Thoros. Edessene militia helped Baldwin's forces discourage Turkish raids in the area. The Orthodox Christian Thoros was so unpopular with the Armenians for his high taxes and poor protection that a mob broke in and murdered him. Baldwin became Count of Edessa and used its treasure to buy the emirate of Samosata for 10,000 bezants. Other crusaders joined Baldwin, were given fiefs, and were encouraged to marry Armenian heiresses as he had. Baldwin allowed the Muslims freedom of worship, but he did not trust their leaders and beheaded Balduk for not cooperating. Others plotting against him were blinded or mutilated, and complicit Armenians had to buy their freedom for as much as 60,000 bezants apiece.

The main army of crusaders arrived at the important city of Antioch in October 1097; but Bohemond, who wanted the city for himself, persuaded the leaders to reject Raymond's proposal to attack immediately. In November Bohemond's forces destroyed the garrison of Harenc, and thirteen Genoese ships arrived at St. Symeon. Turkish sorties made foraging dangerous, and by Christmas food was scarce. Bohemond and Robert of Flanders led 20,000 men into the Orontes valley. After they left, Antioch governor Yaghi-Siyan attacked Raymond's Franks, and losses were heavy on both sides. Dukak of Damascus and Yaghi-Siyan's son Shams led forces that attacked Robert's army. Bohemond's troops helped defeat them; but they returned to the camp by Antioch with little. The winter was cold and wet, and one out of seven crusaders died of hunger. Most of the horses died. Bishop Adhémar got a message to Jerusalem patriarch Symeon on Cyprus, and he sent some food. Many deserted and were brought back by Tancred, including Peter the Hermit. The Byzantine Taticius left and told Emperor Alexius that Bohemond had told him he was in danger, though Bohemond called Taticius a coward, hoping that Antioch would not be restored to the empire.

In February 1098 the Frank cavalry attacked the approaching army of Aleppo's Ridvan, forcing them to flee. In March a fleet sailed into St. Symeon with the English prince Edgar Atheling and siege equipment sent by Alexius. Raymond and Bohemond went to get the equipment and were attacked; but Godfrey came to their aid, and together their armies defeated the raiders, who had 1500 men killed and drowned, including nine emirs. Now the crusaders could blockade Antioch, and castles were built and ruled by Raymond and Tancred. Fatimids from Egypt brought a proposal to recognize the crusaders in northern Syria if the Fatimids could have Palestine; but this was rejected. Alexius was campaigning in Asia Minor; but Bohemond got the leaders to agree to let him have Antioch if the Byzantine emperor did not arrive. The army of Mosul atabeg (regent) Kerbogha was delayed for three weeks trying and failing to take Edessa from Baldwin. Stephen of Blois deserted, but the next day on June 3, 1098 Antioch was secretly betrayed by a Christian named Firouz to Bohemond, and all the Turks in the city were massacred. The Patriarch John was released, and the cathedral of St. Peter was restored.

Shams ad-Daula remained in the citadel, and within four days Kerbogha's army was camped around Antioch in a blockade. The crusaders hoped that Emperor Alexius would relieve them, but he was told by Stephen of Blois that the crusaders at Antioch were probably destroyed. So the Byzantine army retreated to the north, devastating the land to protect their recently increased empire from the Turks. A peasant named Peter Bartholomew claimed that he had a series of visions in which Saint Andrew revealed to him that the lance which wounded Jesus could be found beneath the floor of the cathedral. Bishop Adhémar was skeptical; but Raymond ordered a search that dug up an iron weapon. A priest named Stephen said he had a vision in which the Christ warned the Bishop about the fornication of the crusaders.

Then Peter Bartholomew had another vision in which the crusaders were advised not to pillage the enemy's tents in a coming battle. Many Turks were deserting, and Peter the Hermit was sent to negotiate their withdrawal; but Kerbogha demanded surrender. On June 28, 1098 six armies of crusaders marched out of Antioch to fight the Turks. Dukak of Damascus was the first to retreat, and gradually more Turks left until the rest fled in panic. The crusaders did not stop to plunder the camp but instead slaughtered the Turks. Raymond was ill and commanded those left in Antioch; but by pre-arrangement the Turks surrendered the citadel only to Bohemond, who welcomed the converted Turks into his army.

While Bohemond and Raymond argued over who should govern Antioch, Bishop Adhémar sent Hugh of Vermandois to explain the situation to Emperor Alexius. While Raymond and Adhémar were ill, Bohemond gave the Genoese a charter for a market and a church. When Bishop Adhémar died during an epidemic, the crusaders lost their top spiritual leader. Peter Bartholomew's next vision included a message from Adhémar and Andrew that Bohemond should be given Antioch, and the crusaders should repent and march to Jerusalem; but Raymond still believed that Antioch should be given to the Emperor. Meanwhile Bohemond took in Cilicia by getting Tancred's homage, while Godfrey was given Turbessel and Ravendel by his younger brother Baldwin. Robert of Normandy took over Latakia (Laodicea) from Edgar Atheling; but he governed so badly that he was forced out after a few weeks and was replaced by a Byzantine governor from Cyprus. The crusaders sent a letter to Pope Urban. While gathering supplies in the Orontes valley, Raymond captured Albara; even though they had capitulated, all the Muslims were either killed or sold as slaves. Peter of Narbonne was made the first Latin bishop in the East.

Raymond's and Bohemond's forces besieged Maarat an-Numan. Bohemond promised the defenders refuge; but the men were slaughtered, and the women and children were enslaved. Bohemond tried to spread terror by killing prisoners and roasting their heads. Raymond tried to buy the other leaders with offers of money. Meanwhile the troops of crusaders resented the bickering of their leaders and demanded that they march on Jerusalem, or they would destroy the coveted walls and towns. Finally on January 13, 1099 the army of crusaders was led out of Maarat an-Numan by the barefoot Count Raymond as the town was burned behind them. Godfrey and Robert of Flanders followed them a month later, while Baldwin governed his county of Edessa, and Bohemond ruled at Antioch.

After learning the Turks had been defeated at Antioch, the Cairo vizier al-Afdal for the Fatimids in Egypt invaded Palestine and took Jerusalem from Emir Sokman, who surrendered after a 40-day siege and was allowed to leave. By autumn 1098 the Egyptians had occupied all of Palestine as far north as Beirut. Raymond's crusaders were guided through the Sarout valley, where herds had been driven. The local commander paid for immunity, and knights used that to buy a thousand horses. Wanting to extort money from wealthy Tripoli, Raymond attacked Arqa, while he sent Raymond Pilet and Raymond of Turenne to capture the port of Tortosa. Toulouse count Raymond of Saint-Gilles summoned Godfrey and Robert of Flanders to help with the siege.

Emperor Alexius wrote to the crusaders, whose numbers had greatly dwindled, that he would bring an army if they would wait until the end of June. Yet the Emperor secretly told the Egyptians he was not supporting the crusaders. The Fatimids offered the crusaders free access of pilgrims to holy places; but they rejected that offer too. When Peter Bartholomew urged an assault on Arqa, Arnulf Malecorne of Rohes challenged him to undergo a fire ordeal while carrying the holy lance which resulted in Peter dying twelve days later. In May Raymond abandoned the siege of Arqa, and the Emir of Tripoli got immunity by releasing 300 Christian captives with 15,000 bezants and 15 horses. The crusaders found Ramleh abandoned and left the priest Robert of Rouen in charge of the new see with a garrison.

On June 7, 1099 the crusaders camped by the walls of Jerusalem. The Fatimid governor Iftikar ad-Daula had rebuilt the walls. Before the Franks arrived, he filled in or poisoned the wells outside the city, expelled all the Christians, and sent to Egypt for military help. An old hermit urged the crusaders to attack immediately; but lacking ladders and siege engines, they were repulsed. Six ships brought supplies to Jaffa, which had been abandoned by the Muslims. After learning that a large army was coming from Egypt, the priest Peter Desiderius claimed that the spirit of Adhémar had told him that if they proceeded barefoot around the walls of Jerusalem in repentance they would capture Jerusalem within nine days. As they did so, the Muslims on the walls offended them by desecrating crosses. Preaching by Peter the Hermit and Arnulf of Rohes excited the crusaders.