Raymond Damadian

#21

Posted 08 October 2003 - 10:17 PM

Not winning the NobelRaymond Damadian was conspicuously absent from the medicine prize awardees | By Stephen Pincock

Handing out prizes for scientific achievements is, by its nature, a controversial business. More often than not, assigning credit to an individual for an invention or breakthrough means leaving out others who played an important part.

When the award is as prestigious as a Nobel Prize, the stakes are clearly higher than ever. And in the case of this year's prize for physiology or medicine, given to scientists who played a part in developing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the controversy had already been boiling for years.

That's because the claim of “inventing” MRI has long been the subject of a dispute, largely centering around two US researchers—Paul C. Lauterbur, who jointly won the 2003 prize, and Raymond Damadian, who did not.

The debate over these two men's place in history has been a regular topic of discussion at scientific meetings. A year ago, the Wall Street Journal published a report suggesting that the awarding of a Nobel Prize for MRI had been held up because of the dispute.

“What bothers me,” Nicolaas Bloembergen, the 1981 Nobel laureate in physics, told the Journal's Cameron Stracher, “is that the institute in Stockholm has not yet awarded the prize for this great discovery. I believe this is partly due to controversy over Damadian's role.”

Damadian, a physician born in Queens, NY, was unquestionably a pioneer in the application of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) in medicine, conducting key work on tumors in rats in the early 1970s that predated the experiments by Lauterbur and his co-awardee Peter Mansfield that garnered them this year's prize.

In 1972, he filed a patent application for using nuclear magnetic resonance to scan for cancerous tissue in the human body, which was subsequently awarded. His group was also the first to build an MRI scanner.

In 1988, Lauterbur and Damadian were jointly awarded the US National Medal of Technology for their independent contributions to the field. Any number of Web sites list Damadian as the “inventor” of MRI. He has also been inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Last year, at least, Damadian felt that credit for inventing the MRI should go to “me, and then Lauterbur,” which he was quoted as saying in the Wall Street Journal piece. “If I had not been born, would MRI have existed? I don't think so. If Lauterbur had not been born? I would have gotten there. Eventually.”

So why did the Nobel committee disagree? Primarily, some leading scientists say, because the approach to scanning first proposed by Damadian was surpassed by a technique using gradients in the magnetic field developed by Lauterbur and Mansfield.

An article from the National Academy of Sciences' Beyond Discovery Web site sums up this argument: “An essential technical advance that opened up the ensuing widespread application of NMR to produce useful images was due to chemist Paul Lauterbur, who was then at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. In 1971, he watched a chemist named Leon Saryan repeat Damadian's experiments with tumors and healthy tissues from rats. Lauterbur concluded that the technique was insufficiently informative for locating and diagnosing tumors and went on to devise a practical way to use NMR to make images,” it says.

To put it another way: “The actual implementation of MRI probably better goes to Lauterbur, but the use of MRI for medical problems—I think Damadian deserves some credit for that,” one senior Canadian NMR researcher told The Scientist.

Supporters of Damadian feel that recognition should have come in the form of the Nobel. "Arguably, Raymond Damadian...played at least as much a role in the development of medical MRI as did this year's two winners," one physician told The Scientist.

What all this illustrates, says another prominent Canadian researcher R. Mark Henkelman, professor of medical biophysics at the University of Toronto, is the difficulty of pinpointing the eureka moment in scientific endeavor.

“This is probably one of the hardest prizes, as making MRI a reality in the medical domain involved many, many people,” he told The Scientist. “It's very hard to go back to the beginning and stick your finger on one guy with one bright idea.”

Nevertheless, Henkelman thinks the Nobel committee did the right thing. “I think he [Damadian] had a real insight on NMR and cancer and that there might be differences in tissue with pathology that might show up with magnetic resonance, but that's not what this prize is given for, the prize is given for MR imaging and that really belongs to the other two people.”

Damadian was contacted for this article, but did not comment by the time of publication.

Richard Ernst, winner of the 1991 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for work on nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, takes a philosophical view on the whole thing.

“It's not a very pleasant issue,” he told The Scientist. “There are always arguments about who deserved it most. You have to just live with the facts and the reality and accept your fate.”

Links for this article

H. Cohen, “But what about the others?” The Scientist, 16:20, October 28, 2002.

http://www.the-scien...p20_021028.html

Nobel e-Museum

http://www.nobel.se

S. Pincock, “MRI scientists win Nobel prize,” The Scientist, October 6, 2003.

http://www.biomedcen...ews/20031006/06

OpinionJournal, from the Wall Street Journal Editorial Page

http://opinionjourna...e/?id=110001844

Nicolaas Bloembergen, Nobel Prize in Physics 1981

http://www.nobel.se/...1981/index.html

Technology Administration National Medal of Technology

http://www.technology.gov/medal/

National Inventors Hall of Fame

http://www.invent.org/index.asp

Beyond Discovery

http://www.beyonddis....page.asp?I=134

R. Mark Henkelman

http://medbio.utoron.../henkelman.html

Richard Ernst, Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1991

http://www.nobel.se/...1991/index.html

#22

Posted 08 October 2003 - 10:27 PM

Forget about US, forget about Europe. Good is what is good for Armenia.

Take the money and run!

#23

Posted 10 October 2003 - 11:54 AM

In a Funk Over the No-Nobel Prize

Overlooked MRI Pioneer Lobbies Against Decision

By David Montgomery

Washington Post Staff Writer

Friday, October 10, 2003; Page C01

As the Nobels have been unveiled all week, reporters have been calling up laureates every day and asking where they were when they heard the news, and how does it feel to be a winner. But what about the losers? Where were they and how did it feel?

Raymond Damadian was at his computer at home on Long Island at 5:30 Monday morning, logging on to the Nobel Foundation Web site. This was the precise moment when the prize for medicine was to be announced. And there it was: He immediately saw that the work being honored was magnetic resonance imaging -- MRI -- his field! He knew from colleagues that he had been nominated for the prize this year, and several previous years.

He checked the names of the winners.

"I went from my computer into my bedroom," Damadian said yesterday. "My wife said, 'What happened?' I said they gave it to [Paul C.] Lauterbur and [Sir Peter] Mansfield and they left me out."

How did that moment feel?

A pause.

"Agony," he recalled. "I know the outcome of this is to be written out of history altogether."

He tuned out the inevitable media reports of Lauterbur and Mansfield savoring their own personal leaps into history. "It was too much for me to bear."

But unlike most Nobel also-rans, Damadian is not giving up so easily. Yesterday his MRI manufacturing company on Long Island, Fonar Corp., took out a full-page ad in The Washington Post headlined "The Shameful Wrong That Must Be Righted."

It quoted scientists saying he was robbed. It quoted textbooks attesting to his contribution to the now ubiquitous technology -- 60 million MRI exams were given last year -- that employs high-powered magnets and radio waves to produce images of soft tissue inside the body that once was invisible to doctors unless they cut open the patient.

The ad charged that "inexcusable disregard for the truth has led the [Nobel] committee to make a decision that is simply outrageous," and it provided a clip-out form for supporters to mail protests directly to the Nobel arbiters in Stockholm.

Such ads in the Post typically cost just over $80,000, and Damadian said he will place more in other newspapers.

It's one physician-inventor's campaign to get his name added to the award for medicine before it is officially presented later this year.

"I know that had I never been born, there would be no MRI today," Damadian said.

Nobel selections often result in jealousy and hurt feelings, but a public crusade is rare.

"Usually they don't advertise and usually they don't ask everyone to write us," said Hans Jornvall, secretary of the 50-member Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet, which picks the winner in medicine, speaking from Sweden.

He said Nobel officials never comment on Nobel Prize losers.

"To us," he said, "mankind is divided into two groups of people: those who have got the award and those who have still not got it. . . . The ones who have still not got it we don't say anything about."

Of those who got it, Lauterbur -- at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign -- and Mansfield -- at the University of Nottingham -- Jornvall said: "We think they are excellent laureates."

The Nobel Assembly's statement on the winners said Lauterbur and Mansfield "made seminal discoveries" that "led to the development of modern magnetic resonance imaging, MRI, which represents a breakthrough in medical diagnostics and research."

Scientists in the MRI community are not totally surprised by Damadian's protest. Some said Damadian has always been bold in seeking recognition and has pined for a Nobel Prize. But there are varying views in the scientific community about the proper distribution of credit for developing MRI.

"We are perplexed, disappointed and angry about the incomprehensible exclusion" of Damadian from the prize, said Eugene Feigelson, dean of the college of medicine at SUNY Downstate Medical Center, where Damadian did his work related to MRI. "MRI's entire development rests on the shoulders of Damadian's discovery. . . . "

Damadian's discovery, beginning with experiments in 1969, was that cancerous and normal tissue could be distinguished using a precursor technology then known as nuclear magnetic resonance. In 1977 he developed a scanning machine, called "Indomitable," now owned by the Smithsonian National Museum of American History and on loan to an inventors' hall of fame in Ohio.

Working separately in subsequent years, Lauterbur and Mansfield developed more sophisticated methods to capture images of tissue that were clearer, quicker and easier to use.

"In my opinion, Paul Lauterbur and Peter Mansfield deserve the Nobel Prize," said Alex Pines, an expert in nuclear magnetic resonance at the University of California at Berkeley. "In a leap of creative genius, they came up with the gradient imaging methodology that forms the basis for what today is known as MRI."

Damadian's camp characterizes Lauterbur's and Mansfield's work as technological refinements of Damadian's central insight, while the Nobel Assembly and other scientists say Lauterbur's and Mansfield's breakthroughs were "discoveries" in their own right. The documentation that the assembly used to choose Lauterbur and Mansfield -- and exclude anyone else -- will remain secret for 50 years, under Nobel rules, Jornvall said.

Mansfield could not be reached for comment, and Lauterbur said through his wife that he preferred not to comment on Damadian's claims.

Damadian, 67, grew up in Queens and became a varsity tennis player and an accomplished violinist before getting a medical degree. When he was a boy, his grandmother was dying of cancer in the family's home, and her moans kept him awake at night. Later, as a specialist in internal medicine, he was frustrated that patients could have cancers that were undetectable -- and, doing research with mouse tumors and magnets, he hit on his big idea.

He knows his campaign to get a Nobel this year may be a long shot. Once winners have been announced, the assembly never changes its mind, according to Jornvall.

But Damadian says the battle is bigger than he is. In his view, the Nobel Assembly has become the great arbiter of who goes down in the annals of medicine -- yet its judgments are accountable to no one and not subject to appeal.

His campaign is on behalf of all the losers history might forget.

Staff writer Rick Weiss contributed to this report.

© 2003 The Washington Post Company

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

#24

Posted 23 October 2003 - 08:30 PM

A man on a mission to get share of MRI credit

By James Bernstein, Mark Harrington and Earl Lane

STAFF WRITERS

October 21, 2003

The daily prayer service at FONAR Corp. begins at 9 o'clock to strains of the national anthem. And as they have on weekday mornings for the past decade, a group of FONAR workers and executives head to a small area of a shop floor.

For the next 20 minutes, about 15 people listen as FONAR's human resources director, Fred Peipman, reads Scripture and gives thanks.

"We thank you for Dr. Damadian and his invention and the bread it puts on our tables," Peipman says in closing, referring to FONAR's chairman and founder, Raymond Damadian, an inventor who realized that a phenomenon called magnetic resonance could be useful in scanning tissue for signs of cancer.

It may be an article of faith at the Melville medical technology company that their founder created the MRI scanner. But that's not how it was for the Nobel committee that recently ignored Damadian when it handed out honors for development of the machine.

And now FONAR's leader - a man full of strong opinions and contradictions - is on a crusade to make his case.

The 67-year-old, white-haired Damadian is a multimillionaire, but still lives in a colonial in Woodbury he bought decades ago. He is a trained physician, but favors a theory of creationism over evolution. Though CEO of the company, Damadian's salary is $85,000 and he takes no bonus - and says he will not until the company turns a profit.

And while Damadian's career and company is built around his pioneering work with the MRI, he has been unable to persuade the scientific community that he deserved a Nobel prize to secure his place in medical history.

Hans Jornvall, secretary of the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden that selects the winners of the prize for medicine, said Damadian's actions are unusual. While the assembly has received critical comments on past awards, he said, "I have never seen large-scale advertisements against us before," Jornvall said. The prize decision is final, he said, and based on a careful review of the scientific literature.

"Once we have taken a vote, we have taken a vote," Jornvall said.

And that vote awarded the prize to two others, including a man Damadian has considered a nemesis for the past 30 years, Paul Lauterbur of the University of Illinois. Lauterbur did his prize-winning work while he was at Stony Brook University. The other winner was British citizen Sir Peter Mansfield of the University of Nottingham. It's a decision that most in the scientific community think is correct based on the scientific facts, according to several specialists.

But on Oct. 9 Damadian took out a full-page ad in The Washington Post, followed the next day by ads in The New York Times and Los Angeles Times, blasting the Nobel committee for not giving him a share of the $1.3 million prize for medicine. The ads, which showed an inverted Nobel prize medal, accused the committee of "attempting to rewrite history." The ads asked the public to petition the committee to include him in the prize. Full-page ads ran again yesterday in the New York Times and in Dagens Nyheter, Sweden's second-largest morning newspaper.

Many scientists and others have protested Nobel awards in the 100 years the prizes have been issued, but Damadian's actions were considered audacious by almost any measure.

But then again, Damadian has spent much of his professional life rubbing colleagues the wrong way.

"Damadian deserved to be considered" for the Nobel, said Stephen Thomas, a past president of the American Association of Physicists in Medicine. But Thomas, who assumes the Nobel committee did its homework, added that regarding Damadian: "From the point of view of personality, he hasn't pushed his position in what would be considered, in my view, a logical way. He's always been at odds with the field."

Damadian has never shied away from the limelight, his friends say. The recent controversy he has generated in the medical and scientific community has seemed only to add spark to his step.

On a recent afternoon, Damadian strode briskly into the Sweet Hollow Diner in Melville with all the rumpled glamour of an aging prize fighter, his trademark white mane and mustache turning heads, either from vague recognition or the mistaken sense that he is bull-charging them. Holding a cup of coffee he has carried from his office, he nods genially when the smiling proprietor says he has seen him in the papers again. Damadian tucks himself into a corner booth and continues a monologue that never faltered.

When the waitress asks what he'll drink, he says, "corned-beef sandwich." Later, still speaking, he holds the sandwich like a pointer or a stick of chalk, and a large piece of corned beef swings at the bottom of his sandwich but it never falls off.

The short car ride with a reporter had been something of a journey, Damadian recounting in striking detail the events that led to the rescue of his young Armenian father from the slaughter by the Turks in the Syrian desert during World War I. He remembered not only the names of the specific sections of desert where the shattered family was marched, but the spelling of them, veering out of his lane in his weathered white Continental as he turned to a listener to make a point more emphatic.

The feistiness comes through in the current fight. "There isn't anybody out there who wouldn't give me credit for challenging the establishment," Damadian said the other day in an interview in a cluttered FONAR conference room, a smile crossing his face.

"I've always had to withstand the brickbats," said Damadian.

A Child Prodigy

Damadian has long stood out from his friends and classmates, often taking unpredictable paths.

The son of musical parents, Damadian studied violin at Juilliard for nearly a decade but did not pursue it as a career.

Charlie Brukl, who met Damadian when both were young tennis-playing teenagers growing up in Forest Hills and who is now FONAR's director of materials research, said his friend was always a top student with a serious demeanor.

Damadian graduated from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx and later joined the faculty of the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn.

"He has a determination to succeed beyond and above anybody else I've known in the science and medical community," said Brukl. "If he gets an idea, he rarely lets anyone tell him it can't be done."

People who know Damadian say he is complex, often seemingly contradictory.

A trained scientist, Damadian believes the world is only 6,000 years old and debunks the theory of evolution.

"We are asked to believe all modern life oozed out of the bottom of the sea," Damadian said, warming up to one of his favorite subjects - how the world began. "That's preposterous."

An intensely religious Protestant, Damadian is nonetheless anything but humble. On that issue, Damadian quotes Edmund Burke, the 18th century Scottish philosopher and British parliamentarian, who said, "Evil triumphs when good men do nothing."

By this, Damadian means he could not sit back and allow the Nobel committee to exclude him.

"I'm focused on not being written out of history," Damadian said the other day. "Otherwise, every textbook from here on out will say the MRI was invented by Lauterbur and Mansfield."

And preventing that has become the passion of his life these days, even though Damadian readily concedes there is virtually no chance the Nobel committee will reverse itself and add his name alongside the two others who won this year for medicine.

In fact, he says, he no longer wants a Nobel prize.

"The Nobel prize now has a corrupt significance to me," Damadian said. "It has the stain of Cain on it."

He just wants to let the world know that, according to Damadian and his supporters, he played a key and pivotal role in developing MRI technology, and that he should not be forgotten by history.

Diatribe at a Meeting

In 1969 while at Downstate, Damadian had an opportunity to use a nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer in his biophysics research. He got an idea to build an NMR large enough to scan the human body, so it could detect cancer cells.

In 1971, he published a paper in the journal Science on experiments with lab rats showing that NMR signals from cancerous tissue differed from those of normal tissue.

In medical usage, the MRI technique takes advantage of the fact that the human body, by weight, is about two-thirds water. When the body is exposed to a strong magnetic field, the hydrogen nuclei in the water orient themselves. When submitted to a pulse of radio waves, the energy content of the nuclei changes and as they relax to their previous states, a resonance wave is emitted.

Summaries of the history of MRI typically cite Damadian's early role in recognizing that magnetic resonance could be used in medical diagnosis on body tissues. Damadian's supporters maintain that from that insight, all future developments in MRI flow. But many scientists say that Lauterbur and Mansfield made the conceptual advances that permitted the development of the MRI machines now used around the world.

Damadian, who was awarded a patent on Feb. 5, 1974, for an "Apparatus and Method for Detecting Cancer in Tissue," pursued commercialization of MRI on his own, while Lauterbur was unable to persuade officials of the State University of New York system to apply for a patent based on his early imaging research.

For many MRI specialists, Damadian has long been a controversial figure whose difficult personality and categorical statements regarding his contributions have alienated colleagues who might otherwise feel more sympathy regarding his exclusion from the Nobel prize.

"As I look back, if Dr. Damadian hadn't been so vitriolic in his attacks on other people, I would have argued that he deserved to be included" in the prize, said Dr. Gary Fullerton, an MRI specialist at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center in San Antonio. "He created this situation himself."

Fullerton, founding editor of "The Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging," recalled a scientific meeting in London in 1985. "There was a conscious effort on the part of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine to pull Dr. Damadian back into the fold," Fullerton said.

Ian Young, a British MRI expert who was a local organizer of the meeting, said Damadian "had promised he would behave himself" while serving as moderator of a key session with several hundred scientists in attendance. Instead, Young said, Damadian "started giving this diatribe" against Lauterbur.

"People were absolutely shocked that he did it," Fullerton said. "That sort of behavior really doesn't set well with scientists." Lauterbur declined to discuss any matters involving Damadian.

Dr. David Stark, a radiologist at Downstate, who is a strong backer of Damadian, said his behavior at the London meeting was "inappropriate." But Stark said Damadian deserved recognition by the Nobel committee, whatever his relations with other researchers. "For just being a clumsy, pushy New Yorker, he was screwed," Stark said.

Damadian took on corporations as well as the scientific community, filing patent infringement lawsuits against companies he felt were stealing his ideas. One judgment, upheld by the Supreme Court in 1997, ordered General Electric to pay Damadian $128.7 million.

Damadian said that all of the money from that and other suits has been put back into the company for research and development purposes. Damadian is FONAR's largest shareholder, with about 8 percent of the company's stock. His stock holdings amount to about $6.5 million. Damadian said he also receives "a few hundred thousand dollars" of income a year from the 15 scanning centers he has established around the country.

In the patent case, some experts questioned whether the courts fully understood some of the technical issues being argued.

Damadian points to such rulings as buttressing his arguments, but others are dismissive.

"Scientists don't go around looking for information in patent literature," said Paul Bottomley, an MRI expert at Johns Hopkins University who has worked with Mansfield. "Scientists look at journals."

Weighing the Competing Claims

Thomas, the past president of the American Association of Physicists in Medicine who is also an MRI expert at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center, said Damadian's 1971 paper in the journal Science "really sort of laid the groundwork for using magnetic resonance parameters in diagnosis."

Other scientists already had showed that when atomic nuclei subjected to a magnetic field return to their previous energy levels, their "relaxation" times can be measured in two forms, dubbed T1 and T2, that can give information on the structure of the sample.

Damadian devised a way of using the T1 and T2 measurements to detect cancerous tissue in the body. He surgically removed fast-growing tumors from lab rats and showed that their signals differed from those of normal tissue.

"Damadian's main contribution was to observe that one nuclear magnetic resonance property, relaxation time, was elevated in cancerous tissue compared to normal tissue," Bottomley said.

But several specialists said Damadian's original work had some flaws. As it later turned out, relaxation rates are not a reliable indicator of cancer.

"He made the statement you could distinguish cancer because it has longer relaxation times," Fullerton said. "That's very non-specific. ... Tumors do cause that, but other infections and diseases do the same thing."

And Damadian's design for a scanner used a point-by-point method that proved cumbersome and did not produce useful images. "Damadian had a single spot he was moving the sample through," Bottomley said.

Lauterbur realized he could subject the atomic nuclei to a second, weaker magnetic field along with the first field to produce what is called a magnetic field gradient. That gradient, varying in intensity at different points in the sample, served as the basis for the MRI machines used in medical practice, including even those manufactured by Damadian's own company, experts said. Mansfield further developed the gradient method, showing how the signals could be mathematically analyzed to produce two-dimensional slices of the human body. He also showed how to greatly speed up the imaging process.

Several experts said the Nobel committee made the right decision in awarding the prize only to Lauterbur and Mansfield. "There is a real issue," said one longtime MRI specialist who asked not to be identified because he did not want to tangle publicly with Damadian. "The issue is whether Damadian is correct" in challenging the prize committee.

"The fact that he is obnoxious or aggressive, that doesn't make him unique. The fact that he's in industry rather than academia, that's not the issue. The issue is did the Nobel prize committee fail to include a person whose scientific discoveries were essential to the invention being honored? I think the answer to that is very clear. If what you are trying to honor is the workable imaging machines which are used around the world and have a big role in medicine, it is appropriate to honor the invention which makes it possible. That is the field gradient." Said Bottomley: "Most of the scientists in the field would recognize that the award was correct."

Bottomley and others argue that Lauterbur and Mansfield made the fundamental advances that turned MRI into a practical method now widely used in medicine. "The prize was given for the development of MRI imaging in its present form," Young said. "Raymond contributed nothing to that at all."

Thomas dismissed Damadian's comment to one reporter that if he had not been born, MRI would not exist today. "Nobody is indispensable," Thomas said. "People were working with magnetic resonance in biology before he picked it up."

John Throck Watson, a professor of biochemistry at Michigan State University, said Damadian deserved recognition for making discoveries that spurred the subsequent development of practical imaging devices. He said the Nobel committee had an opportunity to include him, since a prize can be awarded to as many as three people.

Young said the Damadian-inspired controversy may have led the Nobel committee to delay the prize for MRI longer than some specialists had anticipated. "We all put it down to the fact that the committee was aware it was going to be very hard to make an award that would be accepted without a row," Young said. Even if Damadian had won the prize, he said, "I don't think it would have shut Raymond up."

Damadian says that he intends to remain active in the field of medical research, and envisions a day when MRI scanners will be the size of living rooms, allowing doctors to produce large-scale, detailed pictures of the insides of the human body.

"The direction I get from my prayers is to stay the course," Damadian said. "I feel I would be disobeying if I didn't."

Copyright © 2003, Newsday, Inc.

#25

Posted 03 November 2003 - 12:05 AM

#26

Posted 19 January 2004 - 12:15 PM

#27

Posted 19 January 2004 - 12:33 PM

#28

Posted 11 July 2004 - 06:27 PM

TB, I just missed that post of yours. Were you reffering to the "Abusing Cancer Science: The Truth About NMR and Cancer" ? If it is that one, I am really skeptical of the way Hollis put it, as if you consider it as only the source of informations, you're taking the words of one team against the other. (Hollis team was competing with Damadians one).

In any instance, if we take Laurberbur words(which one, as he contradicted himself so many times regarding whom was the causes of his first discovery), that his work was independent from Damadians one, he's idea still came from another Armenian

If Damadian didn't worthed the Nobel so as Lauterbur, because the real advencement came from Peter Mansfield, with the 3D imaging. Lauterbur method was one among many 2D attempts that are not used, and there isn't any clear evidences that Peter Mansfield even used Lauterbur studies. The 3 D imaging tool is used as we speak, the cut in slides used presently are so advenced that Lauterbur method is even not needed, while Damadians T1-T2 is used by any MRI.

Edited by Fadix, 11 July 2004 - 06:27 PM.

#29

Posted 11 July 2004 - 06:28 PM

Yes true Armenian"s," two of them, Saryan and Damadian.

#30

Posted 11 July 2004 - 07:09 PM

http://www.nature.co...r/lauterbur.pdf

It was the phase and frequency encoding and the one using the Fourier Transformation(devlopped by Ernest) that was used with the T1-T2 technic and NOT lauterbur one.

Edited by Fadix, 11 July 2004 - 08:25 PM.

#31

Posted 11 July 2004 - 08:08 PM

#32

Posted 19 August 2004 - 01:39 AM

In any instance, if we take Laurberbur words(which one, as he contradicted himself so many times regarding whom was the causes of his first discovery), that his work was independent from Damadians one, he's idea still came from another Armenian

If Damadian didn't worthed the Nobel so as Lauterbur, because the real advencement came from Peter Mansfield, with the 3D imaging. Lauterbur method was one among many 2D attempts that are not used, and there isn't any clear evidences that Peter Mansfield even used Lauterbur studies. The 3 D imaging tool is used as we speak, the cut in slides used presently are so advenced that Lauterbur method is even not needed, while Damadians T1-T2 is used by any MRI.

I don't want to spend time and energy to bash an Armenian scientist, however lousy I think he may be. I am surprised that, after reading through Hollis' book you can still defend Damadian as a scientist. If 10% of what Hollis wrote were true (and he has pretty direct evidence for more than that), it would be enough to bump Damadian off the Nobel-class (actually would bump him all the way to the bottom of the barrel).

Just a couple of points:

* Hollis did not compete with Damadian on imaging, and even if he did, it's irrelevant; he supplies plenty of evidence to show Damadian's scientific and ethical level.

* Damadian's lack of understanding of basic NMR is absolutely scary.

#33

Posted 02 February 2005 - 07:15 PM

Beyond all else, science is a struggle to push back the frontiers of knowledge and a quest for truth. I am a scientist, and have worked continuously in the fields of cancer research and medical science for 35 years. My doctoral research, conducted between 1971 and 1975 in the laboratory of Dr. Donald Hollis at Johns Hopkins, attempted to verify the claim of Dr. Raymond Damadian of New York that MR measurements on biopsy tissues could be used to identify whether that tissue was normal or cancerous. My research demonstrated, I believe conclusively (and this has been confirmed by the passage of time), that Damadian's initial claim was false, not only in small animals such as rats and mice, but more importantly in humans. After I completed my research, Dr. Lauterbur and others developed the concept of differing relaxation times in tissues into a method to produce images of the internal organs of the human body. While Damadian was perhaps the first to observe the relaxation time difference between normal and cancer tissue in rodents, he was not the first to develop a viable, practical, working magnetic resonance human imaging machine, and as a result he did not share the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 2003 with Lauterbur and Mansfield for this discovery.

Prof. Lauterbur has stated on various occasions that it was experiments he watched me carry out in 1971 (in his lab at New Kensington, PA) that led him to the idea that an image of a body could be created on the basis of MR measurements. Thus I did play a minor role in the discovery of MRI, as did at least a hundred other scientists around the world. I do believe my research was significant in that it helped point others in this field in the right direction, but that is a far cry from the claim that some are making here that I should be considered one of the two Armenian inventors of MRI.

Damadian feels that he was slighted by not being included in the prize, and that his contribution will be written out of the historical record. Nothing could be further from the truth. It is my personal belief that Dr. Damadian's contribution, while very important, did not rise to the superlative level required by the Nobel Committee for this award. I believe that the decision to award the Nobel to Lauterbur and Mansfield was the correct one, and I believe it will stand. Most scientists work hard, day in and day out, with no hope of receiving this highest scientific honor, but that in no way demeans the significance and importantce of their contributions to society and mankind.

For those who wish to get a balanced view of this controversy, the book "Abusing Cancer Science" by Donald Hollis, is essential reading.

Any comments on the above may be addressed directly to me at LASaryan@aol.com.

#34

Posted 02 February 2005 - 09:02 PM

Thank you for the great explanation of events.

#35

Posted 02 February 2005 - 11:29 PM

I would like to clarify few points.

-Firstly, you have stated in your post that some here have made the claim that you were one of the two Armenian inventors of the MRI. The only time this was stated(if I am not wrong), it was by me, as an answer to another members sarcastic post, as a joke.

I will comment the rest later.

Regards

#36

Posted 08 November 2013 - 11:35 AM

2003 Nobel Prize for MRI Denied to Raymond Vahan Damadian

By George B. Kauffman

According to the late Ulf Lagerkvist, a member of the Swedish Academy of Sciences who participated in judging nominations for the Chemistry Prize, “It is in the nature of the Nobel Prize that there will always be a number of candidates who obviously deserve to be rewarded but never get the accolade.” Usually, a losing candidate merely accepts the injustice. But in the case of the 2003 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine of $1.3 million, awarded 10 years ago to University of Illinois Chemist Paul C. Lauterbur (1929-2007) and University of Nottingham (UK) Physicist Sir Peter Mansfield (b. 1933) “for their discoveries concerning magnetic resonance imaging,” the undoubtedly deserving candidate, Raymond Vahan Damadian, M.D. (b. 1936), an American of Armenian descent, did not take this injustice lying down.

A group called “The Friends of Raymond Damadian” protested the denial with full-page advertisements, “The Shameful Wrong That Must Be Righted” in the New York Times, Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and Stockholm’s Dagens Nyheter. His exclusion scandalized the scientific community, in general, and the Armenian community, in particular. Damadian correctly claimed that he had invented the MRI and that Lauterbur and Mansfield had merely refined the technology. On Sept. 2, 1971, Lauterbur had acknowledged that he had been inspired by Damadian’s earlier work.

Because Damadian was not included in the award, even though the Nobel statutes permit the award to be made to as many as three living individuals, his omission was clearly deliberate. The possible purported reasons for his rejection have included the fact that he was a physician not an academic scientist; his intensive lobbying for the prize; his supposedly abrasive personality; and his active support of creationism. None of these constitute valid grounds for the denial.

The careful wording of the prize citation reflects the fact that the Nobel laureates did not come up with the idea of applying nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (the term was later changed to avoid the public’s fear of the word “nuclear,” even though nuclear energy is not involved in the procedure) to medical imaging. Today magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is universally used to image every part of the body and is particularly useful in diagnosing cancer, strokes, brain tumors, multiple sclerosis, torn ligaments, and tendonitis, to name just a few conditions. An MRI scan is the best way to see inside the human body without cutting it open.

The original idea of applying NMR to medical imaging (MRI) was first proposed by Damadian, a physician, scientist, and an assistant professor of medicine and biophysics at the Downstate Medical Center State University of New York in Brooklyn. Growing up in Forest Hills, N.Y., he attended the Julliard School and became a proficient violinist. When he was still a boy, he lost his grandmother to a slow death by cancer. He vowed to find a way to detect this dreaded disease in its early, still treatable stages.

MRI scanners make use of the fact that body tissue contains lots of water (H2O), and hence protons (1H nuclei), which will be aligned in a large magnetic field. Each water molecule contains two protons. When a person is inside the scanner’s powerful magnetic field, the average magnetic moment of many protons becomes aligned with the direction of the field. A radio frequency current is briefly turned on, producing a varying electromagnetic field. This electromagnetic field has just the right frequency, known as the resonance frequency, to be absorbed and flip the spin of the protons in the magnetic field. After the electromagnetic field is turned off, the spins of the protons return to thermodynamic equilibrium and the bulk magnetization becomes realigned with the static magnetic field. During this relaxation, a radio frequency signal (electromagnetic radiation in the RF range) is generated, which can be measured with receiver coils.

Information about the origin of the signal in three-dimensional space can be obtained by applying additional magnetic fields during the scan. These additional magnetic fields can be used to generate detectable signals only from specific locations in the body (spatial excitation) and/or to make magnetization at different spatial locations precess at different frequencies, which enables http://en.wikipedia....i/K-space_(MRI) encoding of spatial information. The 3D images obtained in MRI can be rotated along arbitrary orientations and manipulated by the doctor to be better able to detect tiny changes of structures within the body. These fields, generated by passing electric currents through gradient coils, make the magnetic field strength vary depending on the position within the magnet. Protons in different tissues return to their equilibrium state at different relaxation rates.

Using a primitive NMR machine, Damadian found that there was a lag in T1 and T2 relaxation times between the electrons of normal and malignant tissues, allowing him to distinguish between normal and cancerous tissue in rats implanted with tumors. In 1971, he published the seminal article for NMR use in organ imaging in the journal Science (“Tumor Detection by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance,” March 19, 1971, vol. 171, pp. 1151-1153). Nevertheless, many individuals in the scientific and NMR community considered his ideas far-fetched, and he had few supporters at this time.

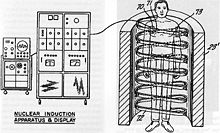

However, Damadian received a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1971 to continue his work. He proposed to use whole body scanning by NMR for medical diagnosis in a patent application, “Apparatus and Method for Detecting Cancer in Tissue,” filed on March 17, 1972 (U.S. Patent No. 3789832, issued Feb. 5, 1974). By February 1976, he was able to scan the interior of a live mouse using his FONAR (field focused nuclear magnetic resonance) method.

In 1977, using his machine christened “Indomitable,” now preserved in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., Damadian tried to scan himself, but the test failed because of his excessive weight. On July 3, 1977, he obtained the first human NMR image—a cross-section of his slender postgraduate assistant Larry Minkoff’s chest, which revealed heart, lungs, vertebræ, and musculature. Minkoff had to be moved over 60 positions with 20-30 signals taken from each position. Congratulatory telegrams poured in from all over the world, including one from Mansfield.

In early 1978, Damadian established the FONAR Corporation in Melville, N.Y., to produce MRI scanners. Later that year he completed his design of the first practical permanent magnet for an MRI scanner, christened “Jonah.” By 1980 his QED 80, the first commercial MRI scanner, was completed.

The MRI imaging industry expanded rapidly with more than a dozen different manufacturers. On Oct. 6, 1997, the Rehnquist U.S. Supreme Court awarded him $128,705,766 from the General Electric Company for infringement of his patent.

Damadian is universally recognized as the originator of the MRI (by President Ronald Reagan, among others) and has received numerous prestigious awards such as the National Medal of Technology in 1988, the same year he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. He was named Knights of Vartan 2003 “Man of the Year,” and on March 18, 2004, he received the Bower Award from the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia for his development of the MRI.

George B. Kauffman is Professor Emeritus of Chemistry at California State University, Fresno, Calif.

#37

Posted 02 February 2014 - 10:20 AM

From: "Moorad Alexanian" <moalexanian@ec.rr.com>

Date: Thu, 30 Jan 2014 23:19:12 -0500

Subject: Letter to the Editor ( American Physical Society News)

http://www.aps.org/p...402/letters.cfm

Controversy Continues Over Picking Nobel Winners

The naming of Nobel Prize winners always raises the specter of

those who may have also contributed but who were not included in

the award. This year's physics prize is no exception (APS News,

November 2013).

This year's winners, François Englert and Peter Higgs, developed

the theoretical mechanism for the origin of mass of subatomic

particles. Others that proposed what is now known as the Higgs

field were the late Robert Brout, Carl Hagen, Gerald Guralnik, and

Tom Kibble.

The prize is not awarded posthumously and may not be shared among

more than three people. These criteria may explain why Brout,

longtime collaborator of Englert, was not included and thus why

only two were awarded the Prize.

The recent passing of Kenneth Wilson (Physics Today, November

2013, page 65) reminds us of a similar case regarding the 1982

Noble Prize in Physics awarded to Wilson for the development of

the renormalization group as applied to critical points and phase

transitions. The names of Michael Fisher, Leo Kadanoff, and

Benjamin Widom come to mind as possible contributors. Surely, the

three-person criterion may have been used in this case.

No doubt, there are many more cases of contention. However, a case

that stands out is that of Raymond Vahan Damadian, an American

medical practitioner and inventor of the first magnetic resonance

scanning machine. Damadian was the first to perform a full body

scan of a human being in 1977 to diagnose cancer. Damadian has

received a multitude of awards for his discoveries. In 2003, the

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded jointly to Paul

C. Lauterbur and Peter Mansfield for their discoveries concerning

magnetic resonance imaging. Surely, there was room here for a

third winner.

Moorad Alexanian

Wilmington, North Carolina

#38

Posted 02 February 2014 - 10:38 AM

Oddly, as he is a devout Christian, and a Scientist he subscribes to Christian Science denomination..

#39

Posted 05 February 2014 - 11:12 AM

Moorad is a very good man perhaps because of his religious leanings. I learned a lot from him during the olden listserve days.

#40

Posted 17 April 2014 - 11:38 AM

0 user(s) are reading this topic

0 members, 0 guests, 0 anonymous users